Exploring the Complexities of Negotiation: Strategies for Successful Intra- and Inter-Team Negotiation in Organizations

and

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, South Korea

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 27 (3) 4

<https://www.jasss.org/27/3/4.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5398

Received: 14-Dec-2023 Accepted: 06-May-2024 Published: 30-Jun-2024

Abstract

Organizational silos pose a common challenge for many companies, as they create barriers to communication, coordination, and resource efficiency. Addressing these challenges necessitates successful negotiation, yet the realm of multi-level team negotiation remains understudied. This research employs a computational simulation model to explore the dynamics of two-level negotiation, encompassing interactions of individuals searching for an agreement within and between teams in the organization. Our model involves individuals and teams with conflicting opinions on mutual interest issues. Within the intra-team negotiation process, the model integrates loyalty-driven opinion adjustments and the influence of the collective opinions of team members on team decisions. Concurrently, the inter-team negotiation introduces parameters reflecting teams’ willingness to negotiate with each other, emphasizing their openness to opinion adjustments. Our findings highlight the importance of individual loyalty, the leader acceptance ratio, and team willingness to negotiate as pivotal factors for achieving successful negotiation. We shed light on the mechanisms involved in two-level negotiations, including both within a team and between teams. This contribution enriches the literature on organizational negotiation and team dynamics in the context of organizational conflict. Moreover, this study advances the field by developing a computational simulation model, laying the groundwork for future studies exploring the multi-level negotiation processes. The insights in this study can equip managers with strategies to foster a win-win mindset for improved team coordination.Introduction

Organizational conflicts such as silos pose significant challenges for companies, including global giants like Amazon. These conflicts arise when different departments or groups within an organization operate independently, pursuing disparate goals, work practices, and priorities. Astonishingly, as a former Amazon performance investigator revealed, "One team rarely knows what another team is doing," while an Amazon manager acknowledged that "Every team functions like an independent company" (Boss 2017). The prevalence of silo structures creates communication barriers, coordination deficiencies, and redundancies, prompting organizations to acknowledge the pressing need for silo mitigation to achieve optimal outcomes.

To address the challenges of organizational conflicts such as silos, it is essential to understand the specific negotiation dynamics within and between teams. In the context of this study, negotiation refers to a complex social process involving two or more parties engaging in communication to reach a mutually acceptable agreement on a matter of mutual interest or concern (Gunia et al. 2016). Negotiation can take many different forms, from formal legal negotiations to informal negotiations between individuals, groups, or organizations, with the aim of achieving a mutually beneficial outcome in line with established goals and interests. Negotiation occurs not only within teams, but also between them; examination of the mechanisms and outcomes of these negotiations is critical. Given the inherent interdependence within organizations, decisions made by conflicting organizational units have a profound impact on negotiation outcomes (Thompson 1967). Thus, negotiation can result in a win-win outcome where all parties benefit, or it can lead to a win-lose or even lose-lose outcome for one or more parties. This study improves our understanding of negotiation dynamics in the context of organizational conflicts and the obstacles they present to negotiations within and between teams rather than directly targeting the mitigation of organizational conflicts.

Despite the increasing recognition of the role of organizational conflicts, such as silos preventing the achievement of outcomes, research has rarely focused on understanding the negotiation dynamics within and between teams in the presence of these organizational conflicts. Existing research has mainly concentrated on either intra-team or inter-team negotiation, failing to consider the interdependence between teams and the potential influence of one negotiation factor on another. We address the crucial question of how negotiation on different levels within organizations influences negotiation on other levels and what factors determine the success or failure of those negotiations. A more comprehensive understanding of negotiation dynamics within and between teams is essential for identifying effective negotiation strategies that can mitigate the negative consequences of organizational silos, promote better coordination, and improve overall performance.

In this study, we delve into the intricacies of negotiation dynamics on two levels: within and between teams. By employing a computational simulation model, we aim to examine negotiation outcomes and their potential impact on individuals, teams, and organizations as a whole. Our objective is to provide insights into the mechanisms of negotiation, especially in the context of organizational conflict. We identify key factors and processes in effective negotiations that lead to win-win outcomes, suggesting practical strategies for managers to improve team coordination and performance.

The theoretical and managerial implications of our results are significant. With a better understanding of the challenges of organizational silos and strategies to mitigate them, managers can foster effective negotiation strategies within and between teams. Our computational simulation model enables in-depth analysis of the mechanisms underlying negotiation and strategies that can help organizations improve team coordination and performance.

Literature Review

Organizational conflict

Organizational conflict is a prevalent phenomenon arising from misaligned or contradictory actions, goals, and disagreements among individuals or groups within the organization (Rahim 2002; Roloff 1987; Siira 2012). Conflicts within the organization emerge due to interdependence among different organizational units during the process of decision-making, including personality differences among coworkers, interdependent tasks among organizational units, incompatible goals, and competition for limited resources (March & Simon 1958; Pondy 1966). Recognizing that personality differences are natural and normal can mitigate potential interpersonal conflict. Conflicts within organizations are often not personal, but rather stem from differing viewpoints or approaches to work (Baron 1989). Jaffe (2000) noted that organizational structure can also create conflict due to interdependence between units. Rahim (2001) provided a detailed classification of sources of organizational conflict, identifying a number of factors related to incompatibilities between organizational sub-units.

Realistic group-conflict theory suggests that organizational conflict arises when units within an organization possess incompatible goals and compete for scarce resources (Campbell 1972; LeVine & Campbell 1972). This theory posits that tension between units is inherent due to the pursuit of their own interests, which is a rational response to limited resources. Additionally, goal interdependence plays a significant role as well. According to Deutsch (1973), goal interdependence, or the extent to which units depend on each other to achieve their goals, influences how each unit behaves and interacts with others. When goal interdependence is high, the decisions of one unit can impact those of others, creating a need for negotiation and balance between units (March & Simon 1958; Pondy 1966).

Organizational conflict exhibits both positive and negative outcomes (Weiss & Hughes 2005). Previous studies have demonstrated that while conflict can have detrimental effects on trust, performance, communication, commitment, and loyalty, which may create workplace incivility, it can also spur innovation, improve decision-making, create new opportunities for problem-solving, and enhance performance (Bagshaw 1998; Darling & Earl Walker 2001; Rahim 2001; Zahid & Nauman 2024). For instance, prior studies have found that organizational conflict independently motivates organizational units to pursue change through engagement in creative projects while avoiding the development of routines (Oehler et al. 2021; Zbaracki & Bergen 2010). This indicates that while not building routines may reduce stability within the organization, it can also foster innovation. Similarly, at the team level, conflict not only uncovers discrepancies and disagreements among members, potentially generating negative emotions and team climate, but it also plays a crucial role in enhancing the team’s conflict resolution capabilities (Cronin & Bezrukova 2019; Weingart et al. 2015). This duality indicates that despite the challenges posed by conflict, it can also be a valuable source of team development and growth, pushing teams towards more effective collaboration and problem-solving strategies, ultimately influencing organizational performance.

To leverage the positive outcomes and mitigate the negative effects, organizations require effective conflict management strategies (Sorenson 1999). A critical aspect of successful conflict management involves creating a supportive environment where conflicts are viewed as opportunities for growth and improvement rather than as disruptive forces. For example, Cronin & Weingart (2007) examine the dynamics of conflict in functionally diverse teams. They emphasize the importance of understanding the diverse perspectives, knowledge, and mental models that organizational units bring from their respective functional backgrounds. By proactively recognizing the potential for representational gaps and the associated challenges in information processing, organizations can implement strategic interventions to bridge these gaps and foster effective communication and collaboration. This proactive approach to managing conflicts in diverse teams not only enhances team performance but also harnesses the valuable pool of knowledge and expertise that functional diversity offers.

To manage conflicts effectively, organizations should consider two major concerns: concern for self and concern for others (Pruitt 1983; Rahim & Bonoma 1979). Concern for self relates to the extent to which an organizational sub-unit prioritizes its own interests and disregards those of others, while concern for others is the degree to which a unit considers the interests of others over its own. The balance between these concerns informs the approach organizational units adopt in navigating conflicts (Deutsch 2002). As shown in Figure 1, these two dimensions describe opposing stances of organizational units in the process of conflict resolution.

Based on a concern for self and concern for others, Rahim & Bonoma (1979) proposed five strategies for handling organizational conflict:

- Integrating strategy: Both parties prioritize their concerns for self and others to find a solution that suits both of them.

- Obliging strategy: One party focuses on the interests of the other party and is willing to accept proposed solutions to maintain a high concern for others.

- Dominating strategy: One party has a high concern for self and a low concern for others, and forces its proposed solution on the other party.

- Avoiding strategy: Both parties have a low concern for self and others, resulting in a failure to satisfy their interests.

- Compromising strategy: Both parties reach an acceptable solution, resulting in a no-win or no-lose situation but ensuring mutual benefit for all parties.

These strategies can be interpreted as individualistic and collectivistic approaches to conflict management (DeChurch et al. 2013). Individualistic strategies, characterized as Avoiding and Dominating, tend to safeguard individual perspectives at the expense of organizational unity. On the other hand, collectivistic strategies, such as Integrating, Compromising, and Obliging, aim to harmonize differing viewpoints while maintaining cohesion within the organization. These conflict-solving strategies are highly associated with negotiation within organizations, as suggested by Thomas (1992).

Negotiation

Negotiation plays a crucial role in managing and resolving conflicts within organizations (Thompson 2015). It involves discussing conflicting interests to reach an agreement or compromise (Pruitt 1998). As conflicts arise from misaligned interests and disagreements among organizational units (Rahim 2002), effective negotiation serves as a key process to address these conflicts and seek resolutions. In the previous section, we explore various conflict resolution strategies, highlighting the need for effective management to leverage positive outcomes and mitigate negative effects. Building upon these strategies, negotiation emerges as a fundamental approach to address conflict interests and find resolutions. To better understand the negotiation strategies employed, Thomas (1992) identified five negotiation strategies (Figure 2) based on assertiveness and cooperativeness, which reflect a unit’s intentions to satisfy its own or others’ needs.

Competing is an uncooperative and assertive strategy where a unit prioritizes its interests over those of others. Collaborating is a highly assertive and cooperative strategy where different units work together to address the concerns of all parties involved. Compromising is a strategy where units find a middle ground. Avoiding involves not addressing the conflict and accommodating and prioritizing others’ interests over one’s own.

In team negotiation, individuals may have different interests, and organizational disunity can impact the negotiation process (Brodt & Thompson 2001; Crump 2005; Keenan & Carnevale 1989). To elucidate the complexity of the situation, we examine two levels of conflict: internal dynamics within a group and interactions between groups.

Sebenius (2013) recommended adopting two levels of negotiation following Robert Putnam’s two-level game theory (1988), as depicted in Figure 3. The two-level game theory postulates that the resolution of international conflicts results from the interplay between domestic and international politics. Domestic groups exert pressure on government officials to align their policies with their interests, while politicians aim to build coalitions among these groups to gain power. National governments must, therefore, balance domestic pressures with the impact of foreign developments on their countries. In this scenario, decision-makers must consider the dynamics of both the domestic and international spheres to resolve conflicts effectively. Similarly, Sebenius (2013) proposed a two-level negotiation model, which stresses the need to align internal negotiations within organizations with external negotiations between organizations. According to Sebenius, a successful negotiation involves not only considering one’s own goals, but also addressing the internal challenges and obstacles faced by the other party. This approach entails effective synchronization of internal and external negotiation strategies to overcome "behind-the-table" barriers and achieve "across-the-table" mutually beneficial outcomes.

Echoing this multidimensional approach, Sanchez-Anguix et al. (2014) delve into the negotiation dynamics of teams within organizations, emphasizing that team-based negotiation necessitates complex decision-making processes that include both intra- and inter-team levels. It shows the necessity for teams to navigate internal interaction while simultaneously engaging in external negotiation. This dual-focus strategy is crucial for teams aiming to secure agreements that are not only internally coherent but also aligned with the broader objectives of the organization.

Building upon the existing literature, this study aims to explore the two-level negotiation dynamics, within and between teams, within the organization, specifically focusing on the strategies employed for effective conflict resolution and collaboration between and within teams. By synthesizing and analyzing previous research, our research objective is to identify key insights and best practices that can inform organizational strategies for navigating conflicts, aligning internal negotiation, and achieving mutually beneficial outcomes. Ultimately, our research aims to provide valuable guidance for organizations in managing and leveraging conflicts to drive strategic success.

Model

To effectively explore how negotiation goals can be achieved, we developed a two-level simulation model that examines both intra- and inter-team processes, filling a research gap in the current literature that often examines these dimensions separately. Our model aligns with foundational work in human-agent negotiation simulations, particularly emphasizing the critical importance of observable strategy variables and the predictive power these variables hold in understanding the aggregated influences on negotiation outcomes (Mell et al. 2018, 2021). These variables operate at both the individual and team levels, offering a comprehensive view of negotiation dynamics. By integrating these strategic variables, our study allows us to gain insights into effective conflict resolution, collaboration, and decision-making in organizations.

Many scholars consider simulation modeling methodology as an effective and systematic way for the development of theory and analysis in the field of management and business. It offers researchers the opportunity to examine the effect of various factors, reflecting the real system, and replicate the same research consistently (Borshchev 2013; Choi & Yang 2024; Edmonds & Hales 2004; Levinthal & Marengo 2016). By employing simulation modeling, we can create a controlled environment to manipulate variables and observe their influence on negotiation. This approach provides a strong theoretical justification for our research, allowing us to generate new insights and advance our understanding of negotiation dynamics in organizations.

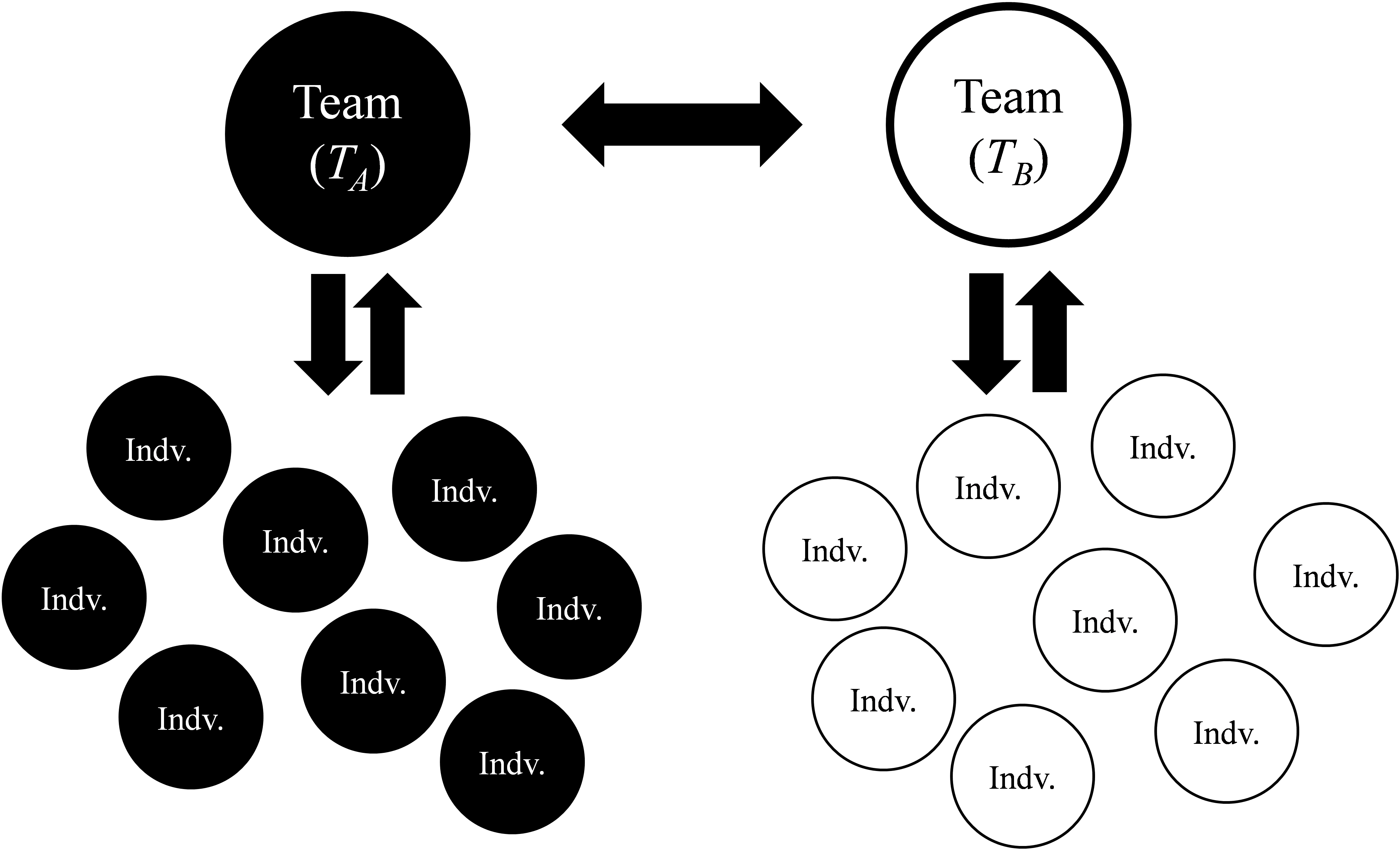

Our model involves two distinct levels of interaction. The first level, intra-team interaction, involves team leaders and members exchanging and integrating opinions to form a collective stance – this is where the leader’s acceptance ratio becomes a key factor during the first level interaction. The second level, inter-team interaction, pertains to how distinct teams engage with each other to decide on maintaining the status quo, negotiate new alternatives, or adopt other opinions. Our research model allows every organizational unit to be aware of what other units with whom one interacts have been doing, consistent with the classic assumption in previous economic and network models (Lee et al. 2016). In our simulation, we emphasize the following roles: individual loyalty toward the team, a leader’s acceptance of team members’ opinions, and willingness to negotiate between teams.

Individual loyalty to the team may play a critical role in team negotiation processes. Previous research has shown that team loyalty can increase cooperation and enhance team performance (Chen et al. 2002). For instance, Reichheld (2006) suggested that improving employee loyalty can motivate individuals to demonstrate cooperative and supportive behaviors toward team or leader decisions, creating a supportive atmosphere and increasing the likelihood of successful negotiation.

The capacity of leaders to value individual team member’s opinions is essential for effective intra-team negotiation, highlighted as a leader’s degree of acceptance for individual opinions in our model. The readiness of leaders to consider these opinions often leads to more successful negotiation outcomes, as collaborative decision-making hinges on open communication (Ristimäki et al. 2020; Saunders 1985). Furthermore, an organizational climate that fosters trust and encourages knowledge-sharing significantly contributes to successful negotiation outcomes (Jain et al. 2015). In this environment, the role of team leaders becomes crucial as their acceptance of individual opinions is foundational to shaping team processes and forming a collective stance on negotiation issues (Zaccaro et al. 2001). By valuing individual opinions, leaders create a supportive atmosphere that enhances negotiation efficacy. Our study investigates leaders’ acceptance of team members’ opinions, recognizing their importance in achieving positive negotiation results.

Loyalty and the leader’s acceptance ratio play pivotal roles in shaping the intra-team negotiation process, guiding teams toward adopting various negotiation strategies. For example, a high acceptance ratio by the leader can align with the Full Unanimity Mediated strategy of Sanchez-Anguix et al. (2013). This approach underscores the leader’s commitment to ensure that every team member’s opinion is integrated into the decision-making process to decide team opinion based on unanimous agreement. Conversely, a low acceptance ratio might lead to the adoption of the Representative strategy, where a single team member is designated to negotiate on the team’s behalf (Sanchez-Anguix et al. 2013). In such scenarios, the level of loyalty within the team can significantly influence members’ dedication to the collective decision-making process and their adherence to the agreed-upon outcomes, impacting the negotiation efficacy.

Additionally, previous research on negotiation and conflict management highlighted the importance of willingness to negotiate. Polzer (1996) argued that a team’s willingness to negotiate is essential for achieving successful outcomes. Guerrero (2020) found a positive association between more cooperative and direct conflict management styles and relational satisfaction. Thus, a willingness to negotiate is essential for achieving positive outcomes.

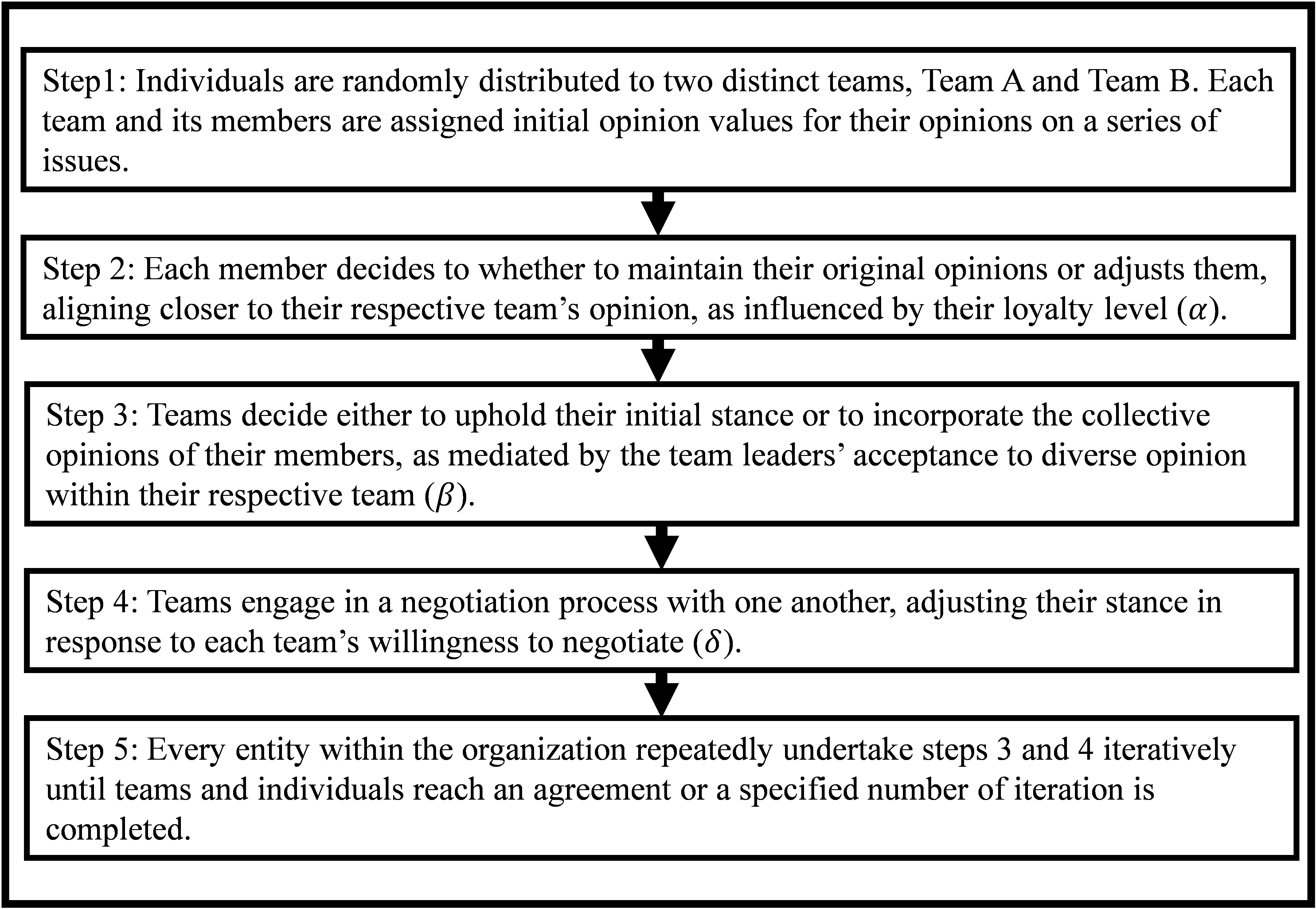

Intra-team interaction

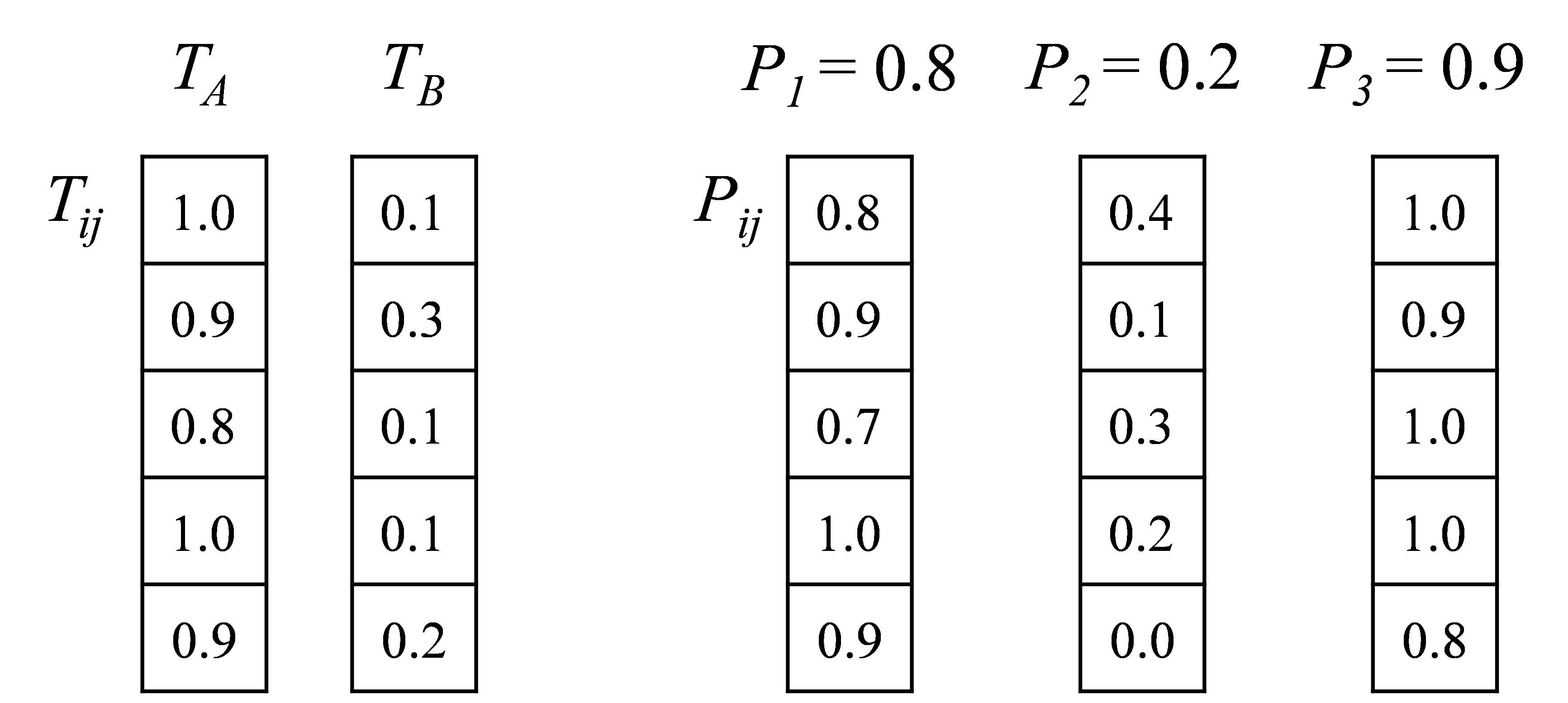

In describing our model, we explore the intra-team decision-making process by highlighting the role of the team leader in guiding team dynamics and decision-making. Our model includes \(N\) individuals, divided into two teams with \(n\) members each. Individuals are randomly assigned to Team A or Team B, where each entity – individual or team – forms its own opinion on \(m\) issues of mutual interest. Before the interaction begins, we assign an initial opinion value to each issue of mutual interest, as indicated by \(j\). For a given issue \(j\), the team’s opinion value is represented as \(T_{Aj}\) or \(T_{Bj}\), depending on whether it pertains to Team A or Team B. We define the opinion of the team (\(T_{A}\) or \(T_{B}\)) as the outcome of the leader’s decision-making process, incorporating the aggregated input, referred to collective opinion, from team member interactions and aligning with the team’s original objectives. Based on the opinion dynamics model of DeGroot (1974), we suggest that individual and team opinions can be quantified on a continuous scale ranging from 0 to 1. This reflects the theoretical framework where opinions are adjusted iteratively towards a consensus, allowing for graduation of stance rather than only a binary position. Simultaneously, we denote the opinion of each individual team member \(i\) regarding the issue \(j\) as \(P_{ij}\). The opinion values for these issues of mutual interest are set to range from 0 to 1, with a midpoint of 0.5 indicating a neutral stance on any given issue. Initially, team members’ opinions on \(j\)-th issue are normally distributed around this midpoint, ensuring that there is no initial bias toward any particular decision within the organization. This normal distribution reflects the diverse perspectives present within the organization, serving as a realistic basis for our simulation of negotiation dynamics.

Figure 4 shows an example of the initial distribution of opinion values among all agents on a shared issue, demonstrating how each team and individual is assigned a unique stance. Teams A and B are each given opinion values, ranging from 0 to 1, that typically contrast setting the stage for potential negotiation or conflict. For instance, Team A’s opinion (\(T_{A}\)) might be set at a high value such as 0.9, indicating a strong stance towards one end of the opinion spectrum, whereas Team B’s opinion (\(T_{B}\)) could be set at a low value like 0.2, indicating a strong stance towards the opposite end.

Figure 5 illustrates how intra-team negotiation goes, with the team leader implied at the center of the team interactions. As the team engages in discussion, influenced by the leader’s direction and the collective dynamics, individual opinions may evolve, potentially aligning more closely with the group consensus or diverging to maintain their distinctiveness. This dynamic is represented by the following equations:

| \[ P_{ij}^{t + 1} = P_{ij}^{t} + \alpha_{i}[P_{i}(T_{Aj}^{t} - P_{ij}^{t})]\] | \[(1)\] |

| \[ P_{ij}^{t + 1} = P_{ij}^{t} + \alpha_{i}[P_{i}(T_{Bj}^{t} - P_{ij}^{t})]\] | \[(2)\] |

Moreover, the opinion of each team (\(T_{A}\) or \(T_{B}\)) is determined by the leader’s decision-making process, which considers the diverse opinions and inputs from the team members. As such, the leaders play a critical role in shaping the team’s stance, and their openness to team members’ opinions is demonstrated in equations (3) and (4), where \(\beta\) indicates the leader’s degree of acceptance of collective opinions of team members at time \(t\):

| \[ T_{Aj}^{t + 1} = T_{Aj}^{t} + \beta[\frac{\sum_{i}P_{i}P_{ij}^{t}}{\sum_{i}P_{i}} - T_{Aj}^{t}]\] | \[(3)\] |

| \[ T_{Bj}^{t + 1} = T_{Bj}^{t} + \beta[\frac{\sum_{i}P_{i}P_{ij}^{t}}{\sum_{i}P_{i}} - T_{Bj}^{t}]\] | \[(4)\] |

In these equations, the value of \(\beta\) signifies the leader’s capacity to integrate the collective opinion formed by individual members into the team’s evolving viewpoint. A \(\beta\) of 0 would imply that the leader maintains the original team opinion irrespective of collective opinions, displaying a decision-making style resistant to influence. On the other hand, a higher \(\beta\) value indicates a leader’s greater acceptance of the collective opinions of team members, indicating a more inclusive and collaborative approach. This mechanism highlights the interactive nature of leadership within the team, where decisions emerge from a balance between the leader’s capacity of leading the team and the evolving collective opinions of team members, with \(\beta\) serving as the moderator in this negotiation process.

Building upon the previous opinion dynamic model by Sobkowicz (2018), our study also excludes direct inter-individual interaction. Instead, we position individuals within a framework that simulates the influence of socially interconnected contexts through being assigned to one of the teams within the organization.

Inter-team interaction

In the realm of inter-team negotiations, our model simulates how separate teams, each with their own internally derived stances, engage with one another to resolve issues of mutual concern. These interactions are pivotal in understanding how organizations, composed of multiple teams with potentially divergent goals and perspectives, navigate toward agreement or compromise.

Figure 6 shows the overall negotiation process within the team, including both intra- and inter-team interactions, engaged over issues of shared interest. The parameter \(\delta\) captures the essence of each team’s strategy by quantifying their willingness to shift from their original position and move towards an agreement:

| \[ T_{EGO,j}^{t + 1} = T_{EGO,j}^{t} + \delta(T_{ALT,j}^{t} - T_{EGO,j}^{t})\] | \[(5)\] |

In our model, we set the number of individuals (\(N\)) and the number of issues (\(m\)) at 1,000 and 10, respectively. All parameter values for our simulations are presented in Table 1. In our simulations, we set parameter values for \(\alpha\) (individual loyalty), \(\beta\) (team members’ opinion acceptance), and \(\delta\) (willingness to negotiate) within a continuous range from 0 to 1, mirroring the continuous scale used for opinion values as influenced by DeGroot‘s model (1974). This range represents the extremes of behavior in each case: a value of 0 corresponds to no loyalty, acceptance, or willingness to negotiate, implying a completely independent or intransigent stance. On the other hand, a value of 1 indicates complete loyalty, acceptance, or willingness to negotiate, suggesting full alignment with the team’s opinion, wholehearted inclusion of team members’ input, or total openness to negotiation with the other team. To explore the gradations between these poles, we have selected specific values – 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1. This allows us to observe the shifts in negotiation dynamics from non-existent, through minimal and moderate, to full engagement, thus providing a comprehensive understanding of how varying degrees of each variable can impact the overall outcome. By incrementing these values, our model captures the dynamic shifts in behavior – from rigid to flexible – offering insights into how different levels of loyalty, acceptance, and negotiation willingness can impact the outcome of negotiations within and between teams.

| Parameter | Remarks | Parameter values analyzed |

|---|---|---|

| \(m\) | Number of issues | 10 |

| \(n\) | Number of individuals within each team | 500 |

| \(N\) | Total number of individuals | 1,000 |

| \(\alpha_{i}\) | Degree of \(i\)-th individual’s loyalty | 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 |

| \(\beta_{A}, \beta_{B}\) | Degree of acceptance of team members’ opinion | 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 |

| \(\delta_{A}, \delta_{B}\) | Degree of willingness to negotiate with another team | 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 |

Figure 7 presents the overall negotiation process of the simulation model developed in our study. The flowchart shows the flow and involvement of various parameters in a two-level negotiation framework. This process is iterative, with entities within the organization cycling through intra-team and inter-team negotiations until consensus is achieved or the simulation reaches the designated number of iterations.

Results

We first analyze negotiation outcomes within each team by examining the impact of two key parameters: individual loyalty towards the team (\(\alpha\)) and the leader’s acceptance ratio of the team members’ collective opinions (\(\beta\)). In this simulation, the leader (who has the power to make decisions) and team members engage in intra-negotiations. In this simulation, successful negotiation is achieved when all organizational units reach an agreement. We define collective opinion as the mean of all team members’ opinions. Thus, the leader’s acceptance (\(\beta\)) quantifies the extent to which the team leader integrates this collective stance into the team’s opinion.

Figure 8 presents the results of separate simulations for different values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), ranging from 0 to 1, over time, in the context of intra-team negotiation. We set the willingness to negotiate with another team (\(\delta\)) as 0 for this simulation. In this research, we consider reaching an agreement to be a successful negotiation outcome that resolves organizational conflicts among organizational units. Reaching an agreement involves a process of reaching a shared understanding among multiple parties by considering their perspectives and finding common ground.

Firstly, our analysis shows that an increase in both individual loyalty and the leader’s acceptance ratio of collective opinions within each team significantly enhances the likelihood of successful consensus within each team. Individual loyalty fosters commitment and trust toward a team’s opinion, while the leader’s acceptance promotes inclusivity and valuing diverse perspectives. These factors may create an environment conducive to effective cooperation and ultimately lead to successful negotiation outcomes within a team.

Also, our results demonstrate the influence of individual loyalty on each team’s opinion formation. When the degree of individual loyalty exceeds the degree of the leader’s acceptance of collective opinions, the team’s opinion after negotiation tends to align more closely with the original team’s opinion. Conversely, when individual loyalty is lower, the team’s opinion afterward tends to converge toward the average of individual opinions. This finding underscores the impact of influential team members and persuasive arguments during the negotiation process.

Furthermore, we examine the time dynamics involved in reaching an agreement within teams, considering the impact of individual loyalty and the leader’s role in accepting the collective opinions of members. We discover that when team members change their opinions only based on their loyalty, reaching an agreement takes longer. This delay happens because each person’s opinion needs to be carefully incorporated into the team’s opinion. On the other hand, when a leader who has the authority to determine a team’s opinion is open to accepting the opinions of team members, the team reaches an agreement faster. It highlights the capacity of leaders to blend individual opinions into the team’s opinion for efficient negotiation within the team. For example, we can think of a scenario in a project team tasked with developing a new marketing strategy. When team members merely align their ideas with the initial team direction out of loyalty, without genuine conviction, the team struggles to form a cohesive plan. Each member’s insights, though minor, accumulate, necessitating thorough discussion and reconciliation. However, when a leader effectively integrates these varying opinions – by organizing brainstorming sessions or anonymous voting on ideas – the team more readily identifies a common strategy that reflects a true consensus, thereby expediting the decision-making process.

Additionally, we figured out that reaching an agreement between teams solely through intra-team interaction is challenging. Our result highlights the crucial role of inter-team interaction in negotiation processes within the organization. Intra-team dynamics might influence inter-team negotiation, but it cannot solely achieve an agreement between two teams.

Building on our findings on intra-team negotiation, we further analyze inter-team negotiation processes over time. To facilitate consensus building, we intentionally set the values of both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) as 0.01, based on our previous findings, which showed that increasing these values promotes quicker consensus-building outcomes. We then explore the impact of each team’s willingness to negotiate with the other team (\(\delta\)), as depicted in Figure 9. The simulation conditions provided four different levels of willingness: 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 for both teams. This may reflect varying degrees of cooperativeness, attempting to satisfy each other’s concerns.

When both teams have a willingness to negotiate set at 0, the negotiation process fails to reach an agreement. This scenario resembles a non-cooperative game, where each team is reluctant to engage in compromise. To address this challenge, it is recommended that each team adopts a strategic approach that emphasizes a cooperative relationship with the other team. By showcasing a willingness to find common ground and demonstrating a more open and collaborative stance, each team can potentially encourage the other team to adopt a similar cooperative approach, leading to a higher level of cooperativeness and a lower level of assertiveness.

On the other hand, when the willingness to negotiate is set at 1 for both teams, the agreement is reached at a point between team A’s and team B’s original opinions. However, the exact outcome is randomly close to either team’s opinion as both teams are open to negotiation and do not rigidly maintain their own preferences. In real cases, this situation can resemble a mixed-strategy game where both assertiveness and cooperativeness are present. In this scenario, each team can adopt a strategy that combines cooperative elements with assertiveness. By actively participating in the negotiation process, each team can influence the agreement point to align more closely with its preferred outcome while also recognizing the need for compromise to maintain a positive relationship with the other team.

When the willingness to negotiate is set at intermediate levels, such as 0.01-0.01 (Team A-Team B) or 0.1-0.1 (Team A-Team B) for both teams, the agreement is achieved at the exact midpoint between team A’s and team B’s original opinions. This scenario resembles a coordination game, where moderate levels of willingness from both sides facilitate a balanced outcome. Here, each team can underscore the benefits of an equitable agreement and highlight the fairness of a midpoint solution. By emphasizing the shared interests and mutual gains that can be achieved through cooperation, each team can increase the likelihood of reaching a satisfactory consensus.

It is important to note that across varying levels of willingness, while values of both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are 0.01, complete adoption of the other team’s opinion or complete imposition of each team’s opinion is not feasible. Instead, the agreement point tends to fall between two original opinions, emphasizing the need for compromise and mutual concessions. The level of willingness for each team directly influences the location of the agreement point. When team A exhibits higher willingness than team B, prioritizing cooperation and addressing team B’s concerns, the agreement point is more likely to align with team B’s original idea. On the other hand, lower willingness from team A, which emphasizes asserting its own concerns, leads to an agreement point closer to team A’s original idea. However, it is still crucial to recognize that in both cases, the agreement point remains between the two original opinions. This highlights the importance of compromise and finding a middle ground that accommodates the concerns of both teams.

Then, how can each team lead the negotiation in the way they desire? We further delve into the dynamics of inter-team negotiation and explore how teams accomplish the negotiation in a manner that aligns with their desired outcomes. Specifically, we focus on the case where a team aims to impose its opinion on the other team fully. In order to do so, we make a modification to intra-team dynamics. Recognizing the importance of maintaining individual loyalty within teams, we set the value of \(\alpha\) at 0.01 to ensure excluding the possibility of turnover or dismissals. However, we adjust the value of \(\beta\) to 0, allowing us to examine the extent to which a team can assert its own concerns and influence the agreement point solely through inter-team negotiation.

While successful negotiation typically involves a balance between assertiveness and cooperativeness (Thomas 1992), we also recognize that each team may have its own preferences and desires that go beyond mutually beneficial outcomes. To explore this aspect, we aim to gain insight into the dynamics of inter-team negotiation under these specific conditions. By studying the interplay between individual loyalty, a leader’s capacity to accept collective opinions, and the possibility of imposing opinions, our research contributes to a broader understanding of negotiation mechanisms and strategies within organizational contexts.

As shown in Figure 10, similar to our previous findings, when both teams have the willingness to negotiate set at 0, the negotiation process fails to reach an agreement. This outcome aligns with the concept of the Nash equilibrium, where neither team has the incentive to change their positions. In this situation, the team should explore alternative strategies that encourage both teams to increase their willingness to negotiate, fostering a cooperative environment conducive to successful negotiation.

When the willingness to negotiate is set at 1 for both teams, the negotiation outcome becomes a random imposition of either team A’s or team B’s opinion. This outcome reflects an accommodating scenario where both teams try to satisfy other’s concerns. In this case, it is essential for both teams to carefully assess the potential gains and losses associated with a random imposition outcome. While it may be advantageous for team A to adopt a cooperative stance and emphasize the value of reaching a mutually beneficial agreement, it is crucial to consider the potential drawbacks of fully adopting team B’s opinion. Similarly, team B should also evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of fully adopting team A’s opinion. By highlighting the benefits of cooperation and mutual concessions, both teams can influence the negotiation process to align more closely with their desired outcomes. This cooperative approach allows for the consideration of each team’s concerns and interests, ultimately increasing the chances of achieving a satisfactory agreement.

Importantly, when either team A or team B has a willingness set to 1, the team with higher willingness fully adopts its partner’s opinion. This outcome demonstrates the influence of a dominant player in the negotiation process. If team A aims to impose its opinion fully, it should strategically increase its willingness to negotiate to a higher level. By doing so, team A can position itself as the dominant player, effectively influencing the negotiation point closer to its partner’s original idea. In the same vein, when team A’s willingness is higher, the agreement point aligns more closely with the partner’s original idea. On the other hand, if team A’s willingness is lower, the negotiation point tends to be closer to team A’s own idea. It is worth noting that these negotiation points are consistently closer to the team’s original opinion compared to situations where a leader’s acceptance of team members’ opinions is set at 0.01. It is because when team A’s acceptance of team members’ opinions is set at 0, indicating a lack of openness to consider their viewpoints, the team remains rigid in its stance during inter-team negotiations with team B. In this scenario, team A solely focuses on imposing its own opinion on team B without considering the perspectives and concerns of its own members.

On the other hand, when team A has a higher acceptance of team members’ opinions, set at 0.01, the team demonstrates a willingness to consider and value the viewpoints of its own members. During negotiations with team B, team A engages in internal discussions and considers the opinions and perspectives of its members. This openness to internal input allows team A to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand and be receptive to potential compromises or adjustments to its own position. By incorporating the perspectives of its members, team A shifts its focus from solely imposing its opinion on team B to actively seeking a mutually agreeable solution that integrates the concerns and viewpoints of both teams. This collaborative approach increases the likelihood of finding common ground and achieving outcomes that satisfy the interests of both teams.

Therefore, a strategic decision to adjust the willingness of both teams can significantly impact the negotiation outcome and align it more closely with their desired position.

By considering these scenarios and the strategies discussed, organizations can enhance their negotiation approaches, increase the likelihood of reaching an agreement, and effectively manage inter-team and intra-team dynamics.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we delve into the dynamics of intra- and inter-team negotiation within organizations, exploring the effects of various factors on negotiation outcomes, such as individual loyalty, team leaders’ acceptance of members’ opinions, and willingness to engage in negotiations. Through a series of simulations, we have uncovered key insights into negotiation dynamics and their implications for organizational strategy.

Within the team, individual loyalty and team leaders’ acceptance of collective opinions are crucial for effective cooperation by contributing to reaching a consensus. For instance, when a team is working on a project, intra-team negotiation could involve members with different perspectives on the project’s direction. If there is a conflict within a team on whether to prioritize cost efficiency or innovation, they may discuss the potential risks and benefits associated with each approach and reach an agreement that balances both aspects. This negotiation process can lead to a clearer understanding of the team’s goals and a mutually agreed-upon strategy (Ristimäki et al. 2020). Organizations should prioritize loyalty and inclusivity to promote successful negotiations. Additionally, the time required to reach an agreement within teams differs based on whether individuals adopt the team’s opinion or the team leader decides to accept collective individual opinions since intra-team negotiations, with diverse viewpoints, require extensive deliberation. For example, consider an organization assessing its approach to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliance, especially when debating investments in renewable energy. Balancing the internal debate on costs against sustainability benefits showcases how negotiation can lead to compromises, like phased renewable energy investments, which align financial concerns with ESG goals. Such outcomes underscore the necessity of providing adequate time for these intra-team discussions, emphasizing that the extent of individual loyalty and inclusivity directly impacts the time to consensus. The ESG compliance challenge illustrates that reaching agreements within teams, especially on complex issues with diverse stakeholder perspectives, demands significant deliberation to accommodate all views. Thus, Organizations should allocate sufficient time for effective intra-team negotiations based on the degree of individual loyalty and team inclusivity.

While successful negotiation within teams is crucial, our findings particularly emphasize the significant role of inter-team interaction. In the context of inter-team negotiation, an example would be that the marketing department may require additional budgetary resources to launch a new advertising campaign, while the finance department argues for cost reduction measures. Through negotiation, leaders from both teams can identify alternative solutions, such as cost-sharing or reallocating existing resources. By understanding each other’s perspectives and finding common ground, they can reach a mutually beneficial agreement that satisfies both departments’ objectives. Achieving an agreement solely through intra-team dynamics may be challenging. Inter-team negotiation plays a pivotal role in reaching an agreement between teams. To facilitate successful negotiation outcomes, organizations should foster inter-team collaboration, establish effective communication channels, and promote a culture of constructive negotiation.

The willingness of teams to engage in negotiation also emerges as an important factor influencing the process and its outcomes. Varied levels of negotiation willingness can result in outcomes resembling non-cooperative games, mixed-strategy games, or coordination games. Encouraging teams to adopt a cooperative approach, emphasizing the benefits of compromise and mutual concessions, increases the likelihood of satisfactory agreements (Jain et al. 2015). Organizations should prioritize creating an environment that encourages teams to embrace a cooperative stance during negotiations.

Moreover, teams can strategically adjust their willingness to negotiate to influence the negotiation process. A higher willingness to negotiate positions a team as a dominant player, exerting greater influence over the negotiation point and aligning it closer to their desired outcome (Guerrero 2020; Polzer 1996). Empowering teams to exercise strategic decision-making during negotiations, leveraging their willingness to shape the negotiation process, can enhance negotiation outcomes and align them with their objectives.

In summary, our study not only sheds light on strategic considerations that can improve negotiation outcomes – such as the pivotal roles of loyalty, inclusivity, and inter-team collaboration – but also significantly advances our understanding by exploring the interactive effects of these variables within the context of organizational negotiations. In particular, our research provides novel insights into the dynamic interplay among individual loyalty, a leader’s commitment to inclusivity, and the collective willingness of teams to engage in negotiation. This study shows how, when integrated, these factors considerably bolster the efficiency and effectiveness of both intra- and inter-team negotiations. By analyzing the synergistic effects of these multilevel variables, our study unveils the intricate mechanisms by which they not only contribute independently to successful negotiations but also exponentially enhance each other’s positive impact when operationalized concurrently. This exploration into the cumulative effect of individual loyalty, a leader’s inclusivity, and team-level negotiation willingness represents the unique contribution of our work, offering a deeper insight to refine their negotiation approaches and more effectively manage the complexities of inter-team and intra-team dynamics.

Our study contributes to the existing literature on negotiation and team dynamics by highlighting the importance of individual loyalty, team leaders’ acceptance of members’ opinions, and willingness to negotiate to achieve successful negotiation outcomes. Also, by developing a two-level simulation model, we expand the methodology for examining the dynamics of multi-level organizational negotiation.

First, our findings on individual loyalty complement those of previous research on team cohesion and job commitment (Chen et al. 2002; Reichheld 2006). Loyal individuals may feel a greater sense of commitment to the team’s goals and values, making them more likely to align their opinions with the team’s position. In contrast, non-loyal individuals may be more likely to stick to their own opinions, even if it means not aligning with the team’s opinion. This could explain our observation that teams with low individual loyalty tended to converge on opinions more slowly, even when the team leader’s acceptance ratio was high. In addition, we observed that teams with high individual loyalty tended to converge on opinions more quickly, even when the team leader’s acceptance ratio was low. These findings suggest that high individual loyalty and job commitment can lead to more cohesive intra-team negotiation and a stronger team stance during inter-team negotiation. Thus, strong individual loyalty can foster greater cohesion within a team, which may make it easier to negotiate and reach an agreement. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of individual loyalty in facilitating successful negotiation outcomes.

Second, our study emphasizes the importance of the team leader’s acceptance of individual opinions. Specifically, a leader who is open-minded and willing to accept team members’ opinions can positively influence inter- and intra-team negotiation and faster consensus-building. Thus, leaders should cultivate an environment of psychological safety and open communication within their teams to promote successful negotiation outcomes. This supports previous findings on leadership styles, particularly transformational or supportive leadership styles. For instance, previous studies argued that transformational leadership fosters a positive work environment that promotes teamwork, open communication, and shared decision-making (Engelen et al. 2015; Schaubroeck et al. 2007). When conflicts arise, negotiation is often necessary to reach a satisfactory resolution for all parties involved. Leaders who practice transformational leadership may be more effective at managing conflicts and negotiating successful outcomes due to their emphasis on communication, collaboration, and positive relationships.

Furthermore, our study highlights the significance of the team’s willingness to negotiate in achieving successful negotiation outcomes. We expand on previous research on negotiation tactics and strategies. Specifically, we find that a team’s willingness to compromise and collaborate with others is positively associated with successful negotiation outcomes. This underscores the value of adopting a win-win mindset in negotiations between teams with conflicts, as doing so can foster positive relationships with other teams and contribute to overall performance.

Our findings also have several practical implications. We emphasize the importance of creating an environment wherein team members feel comfortable expressing their opinions, and leaders encourage open communication and active listening. When individuals feel safe in expressing and maintaining their opinions, they are more likely to engage in negotiation that leads to mutually beneficial outcomes. Also, having a win-win mindset in negotiations can benefit every organizational unit involved in the negotiation. With a win-win mindset, team members actively seek solutions that benefit every unit, trying to avoid a win-lose situation. This can foster collaboration, compromise, and a tendency to find common ground. Under such conditions, team leaders can achieve successful negotiation by creating a supportive and communicative environment while encouraging a win-win mindset. These strategies can help to promote successful negotiation outcomes.

While our research increases our understanding of the dynamics of two-level negotiations within organizations, it is not without limitations, which can be addressed in future research. First of all, our simulation model, though comprehensive, may not capture the full complexity of real-life organizational negotiations. Future research could enrich our findings by integrating additional factors such as power dynamics, cultural differences, and leaders’ personality traits, alongside examining the effects of network structure on negotiation, such as degrees of separation and clustering (Lee et al. 2016). Incorporating empirical validation with real human negotiation data would also bolster the model’s predictive accuracy and theoretical validity.

Furthermore, our adoption of five strategic approaches based on Thompson (2015)‘s ((2015)) does not fully account for the dynamic and anticipatory nature of strategies like boulware, conceder, or tit-for-tat. These strategies, pivotal for adapting and strategically responding to an opponent’s tactics, underscore the necessity for future models to include a broader spectrum of negotiation dynamics that reflect a keen sensitivity to opponents’ strategies. This expansion would not only deepen the model’s theoretical richness but also increase its practical relevance.

Additionally, the model’s reliance on real-valued issues, assuming a continuum between 0 and 1 for opinions, simplifies negotiation scenarios that, in practice, often involve discrete or categorical issues. Expanding the model to accommodate these types of issues would significantly enhance its realism and applicability to a broader spectrum of negotiation contexts.

While our study underscores the importance of reaching agreements as a hallmark of successful negotiation, it does not investigate the consequent effects on organizational performance or team welfare. Future research could shed light on how varying negotiation strategies and outcomes influence overall organizational health and team dynamics.

Overall, while our study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of two-level organizational negotiation, there is still room for exploration in this area. We hope that our findings on intra- and inter-team negotiation inspire future research to improve our understanding of the complexities of negotiation dynamics within and between organizations and to identify strategies to improve negotiation outcomes.

References

BAGSHAW, M. (1998). Conflict management and mediation: Key leadership skills for the millennium. Industrial and Commercial Training, 30(6), 206–208. [doi:10.1108/00197859810232942]

BARON, R. A. (1989). Personality and organizational conflict: Type A behavior pattern and self-monitoring. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 44, 281–297. [doi:10.1016/0749-5978(89)90028-9]

BORSHCHEV, A. (2013). The Big Book of Simulation Modeling: Multimethod Modeling with AnyLogic 6. AnyLogic North America.

BOSS, J. (2017). Silos are killing Amazon’s potential. Don’t let them kill yours. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffboss/2017/09/18/silos-are-killing-amazons-potential-dont-let-them-kill-yours/?sh=2a77a8305fbc.

BRODT, S., & Thompson, L. (2001). Negotiating teams: A levels of analysis approach. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5(3), 208–219. [doi:10.1037//1089-2699.5.3.208]

CAMPBELL, D. T. (1972). On the genetics of altruism and the counter-Hedonic components in human culture. Journal of Social Issues, 28(3), 21–37. [doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00030.x]

CHEN, Z. X., Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J.-L. (2002). Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: Relationships to employee performance in China. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(3), 339–356. [doi:10.1348/096317902320369749]

CHOI, M., & Yang, J. S. (2024). How allocation of resources and attention aids in pursuing multiple organizational goals. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 30, 101–125. [doi:10.1007/s10588-023-09377-4]

CRONIN, M. A., & Bezrukova, K. (2019). Conflict management through the lens of system dynamics. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 770–806. [doi:10.5465/annals.2017.0021]

CRONIN, M. A., & Weingart, L. R. (2007). Representational gaps, information processing, and conflict in functionally diverse teams. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 761–773. [doi:10.5465/amr.2007.25275511]

CRUMP, L. (2005). For the sake of the team: Unity and disunity in a multiparty Major League Baseball negotiation. Negotiation Journal, 21(3), 317–342. [doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.2005.00067.x]

DARLING, J. R., & Earl Walker, W. (2001). Effective conflict management: Use of the behavioral style model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(5), 230–242. [doi:10.1108/01437730110396375]

DECHURCH, L. A., Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Doty, D. (2013). Moving beyond relationship and task conflict: Toward a process-state perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 559–578. [doi:10.1037/a0032896]

DEGROOT, M. H. (1974). Reaching a consensus. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69(345), 118–121. [doi:10.1080/01621459.1974.10480137]

DEUTSCH, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

EDMONDS, B., & Hales, D. (2004). When and why does haggling occur? Some suggestions from a qualitative but computational simulation of negotiation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 7(2), 9.

ENGELEN, A., Gupta, V., Strenger, L., & Brettel, M. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation, firm performance, and the moderating role of transformational leadership behaviors. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1069–1097. [doi:10.1177/0149206312455244]

GUERRERO, L. K. (2020). Conflict style associations with cooperativeness, directness, and relational satisfaction: A case for a six-style typology. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 13(1), 24–43. [doi:10.1111/ncmr.12156]

GUNIA, B. C., Brett, J. M., & Gelfand, M. J. (2016). The science of culture and negotiation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 78–83. [doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.008]

JAFFE, D. (2000). Organizational Theory: Tension and Change. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

JAIN, K. K., Sandhu, M. S., & Goh, S. K. (2015). Organizational climate, trust and knowledge sharing: Insights from Malaysia. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 9(1), 54–77. [doi:10.1108/jabs-07-2013-0040]

KEENAN, P. A., & Carnevale, P. J. (1989). Positive effects of within-group cooperation on between-group negotiation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19(12), 977–992. [doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb01233.x]

LEE, J., Song, J., & Yang, J. S. (2016). Network structure effects on incumbency advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1632–1648. [doi:10.1002/smj.2405]

LEVINE, R. A., & Campbell, D. T. (1972). Realistic group conflict theory. In R. A. LeVine & D. T. Campbell (Eds.), Ethnocentrism: Theories of Conflict, Ethnic Attitudes and Group Behavior. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

LEVINTHAL, D. A., & Marengo, L. (2016). Simulation modelling and business strategy research. In M. Augier & D. J. Teece (Eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management (pp. 1–5). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. [doi:10.1057/978-1-349-94848-2_710-1]

MARCH, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

MELL, J., Beissinger, M., & Gratch, J. (2021). An expert-model and machine learning hybrid approach to predicting human-agent negotiation outcomes in varied data. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces, 15(2), 215–227. [doi:10.1007/s12193-021-00368-w]

MELL, J., Lucas, G., Mozgai, S., Boberg, J., Artstein, R., & Gratch, J. (2018). Towards a repeated negotiating agent that treats people individually: Cooperation, social value orientation, & machiavellianism. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents. [doi:10.1145/3267851.3267910]

OEHLER, P. J., Stumpf-Wollersheim, J., Welpe, I. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2021). Beyond the truce: How conflict affects teams’ decisions whether to enact routines or creative projects. Industrial and Corporate Change, 30(3), 799–822. [doi:10.1093/icc/dtaa053]

POLZER, J. T. (1996). Intergroup negotiations: The effects of negotiating teams. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 40(4), 678–698. [doi:10.1177/0022002796040004008]

PONDY, L. R. (1966). A systems theory of organizational conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 9(3), 246–256. [doi:10.2307/255122]

PRUITT, D. G. (1983). Strategic choice in negotiation. American Behavioral Scientist, 27(2), 167–194. [doi:10.1177/000276483027002005]

PUTNAM, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization, 42(3), 427–460. [doi:10.1017/s0020818300027697]

RAHIM, A., & Bonoma, T. V. (1979). Managing organizational conflict: A model for diagnosis and intervention. Psychological Reports, 44(3suppl), 1323–1344. [doi:10.2466/pr0.1979.44.3c.1323]

RAHIM, M. A. (2001). Managing Conflict in Organizations. Santa Monica, CA: Quorum Books.

RAHIM, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 13(3), 206–235.

REICHHELD, F. (2006). The Ultimate Question: Driving Good Profits and True Growth. Harvard Business School Press.

RISTIMÄKI, H. L., Tiitinen, S., Juvonen-Posti, P., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2020). Collaborative decision-making in return-to-work negotiations. Journal of Pragmatics, 170, 189–205.

ROLOFF, M. E. (1987). Communication and conflict. In C. R. Berger & S. H. Chaffee (Eds.), Handbook of Communication Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

SANCHEZ-ANGUIX, V., Aydogan, R., Julián, V., & Jonker, C. M. (2014). Unanimously acceptable agreements for negotiation teams in unpredictable domains. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 13(4), 243–265. [doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2014.05.002]

SANCHEZ-ANGUIX, V., Julián, V., Botti, V., & Garcia-Fornes, A. (2013). Studying the impact of negotiation environments on negotiation teams’ performance. Information Sciences, 219, 17–40.

SAUNDERS, H. H. (1985). We need a larger theory of negotiation: The importance of pre-negotiating phases. Negotiation Journal, 1(3), 249–262. [doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.1985.tb00313.x]

SCHAUBROECK, J., Lam, S. S., & Cha, S. E. (2007). Embracing transformational leadership: Team values and the impact of leader behavior on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1020–1030. [doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1020]

SEBENIUS, J. K. (2013). Level two negotiations: Helping the other side meet its “behind‐the‐table” challenges. Negotiation Journal, 29(1), 7–21. [doi:10.1111/nejo.12002]

SIIRA, K. (2012). Conceptualizing managerial influence in organizational conflict - A qualitative examination. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 5(2), 182–209. [doi:10.1111/j.1750-4716.2012.00096.x]

SOBKOWICZ, P. (2018). Opinion dynamics model based on cognitive biases of complex agents. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 21(4), 8. [doi:10.18564/jasss.3867]

SORENSON, R. L. (1999). Conflict management strategies used by successful family businesses. Family Business Review, 12(4), 325–340. [doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00325.x]

THOMAS, K. W. (1992). Conflict and conflict management: Reflections and update. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(3), 265–274. [doi:10.1002/job.4030130307]

THOMPSON, J. D. (1967). Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory. London: Routledge.

THOMPSON, L. L. (2015). The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator. London: Pearson.

WEINANS, E., van Voorn, G. A. K., Steinmann, P., Peronne, E., & Marandi, A. (2024). An exploration of drivers of opinion dynamics. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 27(1), 5. [doi:10.18564/jasss.5212]

WEINGART, L. R., Behfar, K. J., Bendersky, C., Todorova, G., & Jehn, K. A. (2015). The directness and oppositional intensity of conflict expression. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 235–262. [doi:10.5465/amr.2013-0124]

WEISS, J., & Hughes, J. (2005). Want collaboration. Harvard Business Review, 83(3), 93–101.

ZACCARO, S. J., Rittman, A. L., & Marks, M. A. (2001). Team leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4), 451–483. [doi:10.1016/s1048-9843(01)00093-5]

ZAHID, A., & Nauman, S. (2024). Does workplace incivility spur deviant behaviors: Roles of interpersonal conflict and organizational climate. Personnel Review, 53(1), 247–265. [doi:10.1108/pr-01-2022-0058]

ZBARACKI, M. J., & Bergen, M. (2010). When truces collapse: A longitudinal study of price-adjustment routines. Organization Science, 21(5), 955–972. [doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0513]