HUMAT: An Integrated Framework for Modelling Individual Motivations, Social Exchange and Network Dynamics

, , , , ,

and

aUniversity College Groningen, Center for Social Complexity Studies, The Netherlands; bNORCE Norwegian Research Centre AS, Norway; cDepartment of Governance and Innovation, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; dDepartment of Sociology/ICS, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; e College of Economics and Management, Huazhong Agricultural University, China; f Information and Computational Sciences Department, The James Hutton Institute, United Kingdom

Journal of Artificial

Societies and Social Simulation 28 (1) 4

<https://www.jasss.org/28/1/4.html>

DOI: 10.18564/jasss.5611

Received: 20-Sep-2023 Accepted: 22-Jan-2025 Published: 31-Jan-2025

Abstract

In this paper we present HUMAT, an integrated modelling framework that supports the simulation of social dynamics. HUMAT integrates theoretical ideas about human motives, cognitive dissonance, individual and social decision strategies, and the processes of influence that take place in networked communities. As such, HUMAT provides a generic model that can be implemented in a wide variety of cases dealing with opinion and behaviour dynamics in a social context, be it the adoption of a physical innovation or the promotion of an attitude in an online platform. The multi-theoretical background of HUMAT also provides a perspective on what types of qualitative and quantitative data can be used to parameterise real cases. This paper aims to provide an overview of the different processes modelled in HUMAT. Three applications are used to illustrate how HUMAT can be used to simulate and study social dynamics. The validation of the HUMAT framework is discussed in the context of the dynamic theory of social complexity.Introduction

The need for theoretically plausible agent frameworks

Debates in communities, polarisations in society, the growth of collaborative networks, the diffusion of new social practices and product adoption are all examples of societal processes that display complex social dynamics. These dynamics emerge from different types of interactions between heterogeneous individuals connected by various types of dynamic networks. Take the example of a municipality that is planning to reduce car traffic in the city centre in order to encourage walking and cycling. Some people will be very involved in discussing this issue and will raise their voices at meetings organised by the municipality. They may read about successes and failures in other cities, and share their opinions and information widely, for example on the internet. Other people may be more likely to follow the opinions of their friends in the pub, or the position of a person they consider reputable, without thinking too much about the issue.

Thus, in such social processes, many people with different perspectives and interests, influence each other to a greater or lesser extent. They may exchange arguments, persuade others resulting in attitude change, and set a norm through exemplary behaviour. The large scale of the social processes, the often considerable time involved in these dynamics, their uniqueness with respect to special circumstances and conditions, make it methodologically very difficult to conduct controlled experiments in complex field settings. In addition, experimenting with societal dynamics can be ethically questionable if people are unaware of the experiment or participate involuntarily. It is therefore understandable that social simulation is becoming increasingly attractive as a tool for experimentation with the social dynamics of complex societal phenomena.

Simulations of social dynamics can contribute to our understanding of the possible scenarios that may emerge from a particular planning situation. For example, if a municipality is considering a policy to reduce car traffic, it would be valuable to identify the risks of polarisation between different interest groups, and to explore how local democratic processes can be supported by information sharing and providing platforms for discussion on the implementation of plans. This would support the identification of promising approaches to engaging communities in planning processes and could strengthen local democracy (Jager & Yamu 2020).

An important challenge for such simulation models is to capture sufficiently realistic behavioural dynamics. To understand the impact of intended (e.g., policy interventions) or unintended events (e.g., crises) on societal dynamics, it is crucial that a simulation considers people’s different motives, the processes of attitudinal (resistance to) change, and the normative and informational influences that spread through evolving networks. Only if the simulated social dynamics are sufficiently realistic will these models be meaningful in terms of contributing to the discussion of possible policy scenarios and how to support democratic processes in communities.

This raises the critical question of what drivers and psychological processes need to be represented when modelling social dynamics in communities to make these models trustworthy and useful. Many behavioural and psychological drivers and processes play a role in the social dynamics. For example, consider a city with a lot of car traffic and an increasing number of cyclists. If a group of people lobbies for a reduction in car traffic to make their city more bike friendly, it is because they expect this to improve their lives, and perhaps also the lives of others in the city. These expected improvements may relate to their personal experience of road safety, but also to their general values about a sustainable future. Expectations thus relate to the different needs that people have and how these needs will be (dis)satisfied if a city becomes more bike friendly. People’s attitudes and opinions will be based on their current satisfaction of multiple needs and their expectations of how it might change after the implementation of a plan. For example, some people may be convinced by a reputable person that reducing car traffic is bad for business and will hurt the economy. If someone thinks this argument is valid and important, they may also discredit dissonant information about the negative impact of cars on air quality and road safety in order to reduce cognitive dissonance. Some may listen primarily to their friends’ beliefs of, conforming to the group rather than risk being ridiculed for having a different opinion. Others may become very vocal about the issue and try to persuade people in their environment, sometimes even in violent ways. Those with similar opinions may connect in interest groups, lobbying at the political level or engaging in street protests. Finally, incidents such as conflicts between cyclists and car drivers and serious accidents involving pedestrians or cyclists, can lead to intensive debates, both in person and on social media.

The above example illustrates that several behavioural and psychological processes play a role in social dynamics: the different needs that drive the desire for change (or not), the immediate rewarding (or punishing) experiences that people have when they perform a behaviour, the attitudes that a person has, the motivation that a person has to speak up, the persuasive power that they have, their adherence to norms, their handling of dissonant information, the activation of certain cognitions by critical events and the formation of networks of people with similar interests. All of these drivers and processes can be linked conceptually to the many behavioural and psychological theories that are available in the social sciences. To name a few key theories, Maslow (1954) and Max-Neef (1992) provide theories on human needs, Pavlov (1927) provided a theory on (classical) conditioning, Skinner (1953) on operant conditioning, Festinger (1957) proposed the cognitive dissonance theory on resolving internal conflicts, Bandura (1962) proposed a theory on social learning and imitation, Cialdini et al. (1991) developed a theory on normative conduct, Ajzen (1985) integrated attitudes, social norms and behavioural control in the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Petty & Cacioppo (1986) provide a theory on communication and persuasion.

These theories, and many other theories, have already been used to inform social simulation models that address specific processes and social dynamics. However, because we need to implement several of these drivers and processes simultaneously in a social simulation modelling context, the challenge is to formally integrate them into a coherent framework. This requires the development of an integrated model framework that describes how these drivers and processes are connected and interact.

The need for integrated social simulation models of human behaviour

Over the years, many of the behavioural rules of agents in social simulation models have been informed by psychological and behavioural theories. Much progress has been made in bringing these theories “computationally alive” through implementations in agent-based models (Gilbert & Troitzsch 2005). This opened the possibility of developing a dynamic theory of social psychology (Nowak et al. 2013; Nowak & Vallacher 1998). In this respect, important contributions are being made to the quest for a social science that is capable of “growing” emergent societal phenomena, referred to as “generative social science” (Epstein 2006).

The implementation of behavioural and psychological theory in social simulation models is an increasingly common practice, as it adds realism to the social dynamics that the models can generate. However, a number of challenges remain in explicitly implementing theory in social simulation models (Davis et al. 2018; Jager 2017; Poile & Safayeni 2016; Schlüter et al. 2017; Schwarz et al. 2020). Four key problems can be identified in the use of existing theories in social simulation models.

First, most science theories of human decision-making are rather descriptive in nature (Schwarz et al. 2020). As a consequence, they do not provide sufficient detail for unambiguous implementation in simulation models (Poile & Safayeni 2016). Sometimes the theories are not clear enough to derive testable hypotheses from them (Sullivan 2002) or to make a clear comparison between competing explanations (West et al. 2019). As a consequence, the implementation of a particular theory can be done in different ways, and the choices for a particular implementation can have a significant impact on the behaviour of the model (Muelder & Filatova 2018).

Second, there are many overlapping theories in some domains, such as theories on opinions, perception, learning, persuasion, and attitude formation. The level of aggregation is also different, ranging from more detailed cognitive theories to more aggregated theories on human interaction. This makes it difficult to obtain a clear theoretical overview of human activities and to identify theories that can be applied in specific contexts (Schlüter et al. 2017).

Third, empirical studies based on theoretical frameworks shed light on causal relationships between key concepts. For example, a positive attitude towards the expected outcomes of a plan, e.g., closing a road in a park to cars, is likely to have a positive effect on voting for the closure in a referendum. While such attitude-behaviour relationships can be identified, the predictive power may be low because the relationship may be obscured by many other mechanisms that are not controlled for in empirical studies. For example, if a person is less involved, because, for example, they do not live near to the park, the attitude may not lead to the decision to vote. Also, if people are engaging in habitual behaviour, such as driving a car to work, a positive attitude towards cycling through the park may not be sufficient to actually change commuting behaviour. Information about the full causal mechanisms leading to behaviour is often lacking, so it is a challenge to develop agent rules that allow for a complete and valid representation of real-world human behaviour.

Fourth, recognising that social dynamics in communities address many drivers and processes simultaneously forces the modeller to link different theories that are not formally linked in existing theoretical approaches. While the more traditional social sciences have developed many theories on human cognition, social psychology and the sociology of networks, there are no tested meta-theories that conceptually integrate these different levels into a single framework. This is partly due to the limited number of variables that can be studied in combination in empirical experimental research designs. A “grand theory of human behaviour” that would integrate different theoretical drivers and processes into a single framework is thus still lacking. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1985) is one of the few theories combining different processes, but does not provide complete causal mechanisms for the variety of contexts in which it can be applied (Muelder & Filatova 2018).

However, while social simulation models are increasingly grounded in behavioural theory, we are also observing an increased interest in developing social simulation models that integrate different mechanisms and processes, as they allow for the modelling of more complex societal dynamics.

Computational social science offers critical opportunities for developing such integrated social models, as the agent-based computational foundation is capable of implementing different types of causal relationships (Antosz et al. 2022), and allows the representation of the micro-macro linkages, thus closing the loop between cognition, social interaction and network dynamics. In this way, social simulation opens up the possibility of formally (causally) linking different levels of theory and thus developing models that integrate theoretical notions from individual cognition, social interactions and network properties. Most importantly, from a social perspective, social simulation modelling opens up new perspectives for studying how humans behave in groups under tightly controlled experimental conditions.

Several computational frameworks aimed at integrating cognition with social activity are already available, such as the Consumat (Jager 2000), FEARLUS, which integrates cognition and social cognition through case-based reasoning (Izquierdo et al. 2004), dynamical affinity model (Bagnoli et al. 2007; Carletti et al. 2008), Agent_Zero (Epstein 2014), Polias (Brousmiche et al. 2016), BayesAct (Schröder et al. 2016), and co-development of beliefs and social networks (Edmonds 2019). These integrated approaches are highly relevant, as they aim to connect different processes in a causal framework that supports the modelling of drivers and processes that are causally connected. As such, these integrated models support the call for a dynamic social science (Nowak & Vallacher 1998) or generative social science (Epstein 2006).

Because individual tipping points take place in a social setting, and the normative context is important, such changes often lead to a motivation to persuade others in the personal network of the benefits of the new behaviour, partly also to resolve dissonances resulting from engaging in behaviour that deviates from the group norm. A contribution of HUMAT is its capacity to model people’s motivation to speak up and try to persuade others of their opinions, which is important for understanding dynamics such as social tipping points. In addition, if a change in behaviour causes lasting friction (social dissonance) with family, friends and colleagues, the frequency of interaction may be reduced or stopped, and new friends with similar perspectives and behaviour may be made, thus addressing dynamics in social networks such as clustering and separation.

The modelling of these processes requires a framework that can unite insights from social science theories addressing the micro, meso and macro levels. HUMAT aims to link these different levels in order to simulate processes emerging from interactions between individual cognitions, social interactions and social networks.

Linking different theories in a computational model should be done carefully, as simply adding more theoretical detail to a model can lead to the growth of models that are unbalanced in terms of details at different levels, and can produce simulated dynamics that are difficult to understand. Voinov & Shugart (2013) refer to models that are over ambitious in integrating many theoretical components “integronsters”. However, making a model too simple also runs the risk of failing to adequately represent key mechanisms. Thus, Janssen (1996), paraphrasing Albert Einstein on the need for simple theories, wrote: “A model should be as simple as possible, but not simpler than that”.

In the context of the aforementioned social dynamics in communities, we face a number of challenges in modelling the processes that link the levels of individual need satisfaction, attitudes, social interaction, persuasion and network topology dynamics. While the integrated models mentioned above link different drivers and processes, we still identify behavioural/psychological drivers and processes that need to be included in a model to be able to model some essential behavioural and social dynamics within communities. In particular, the theoretical ideas of difficult trade-offs in need satisfaction, the resulting cognitive dissonance and the relationship with persuasion and reputation are important in addressing the processes of opinion and behavioural change in communities. Here, HUMAT aims to make an important contribution by modelling cognitive dissonance resulting from trade-offs between different needs. Cognitive dissonance allows for the modelling of individual tipping points. This refers to situations in which people initially resist changing their behaviour by emphasising its benefits and denying its negative effects. However, when the disadvantages become too pressing, the dissonance can be more effectively reduced by changing behaviour. This change in behaviour will also lead to a cognitive reframing in which the negative consequences of the old behaviour are acknowledged and the benefits of the new behaviour are emphasised. Examples of such personal transitions include, for example, quitting smoking, switching to a vegan diet or converting to a new religion/worldview.

For the HUMAT1 integrated model presented here, we therefore decided not to start by selecting a number of existing theories and trying to formally connect them, as this would run the risk of creating an unbalanced “integronster”. Rather, we started by connecting the key drivers and processes in a relatively simple dynamical framework. HUMAT has been developed as an integrated framework to support the development of social simulation models that address a number of key processes on both the micro and macro level. It supports the implementation of social simulation models for different cases, and provides a perspective for different types of data that can be used to parameterise the model. Thus, HUMAT can be considered as a more generic framework, and the basic implementation in code has supported the development of computational models in several different cases, such as a referendum on making a park car-free, an island transitioning to energy independence (Bouman et al. 2021; Jager et al. 2024), opinion dynamics and polarisation on Covid-19 vaccinations (Li & Jager 2023) and adherence to social distancing rules during a pandemic (De Vries et al. 2023).

The HUMAT Framework

An integrated psychologically plausible model

Simulating the interaction of people in communities (physical or virtual), requires a modelling framework that can capture the key social dynamics that take place. Real-world social dynamics, such as social innovations (SI), opinion dynamics and behavioural transitions (e.g., Nyborg et al. 2016), involve the behaviour and communication of many different individuals connected in social networks. They make decisions about their behaviour based on their knowledge, interests and values, share information with others, and are susceptible to norms. They are repeatedly confronted with difficult choices, often having to make trade-offs between short-term gratification, social impacts of choices and personal values. Interactions between individuals lead to the diffusion of new behaviours, the formation of opposite opinion groups, and the emergence of tipping points that give dominance to certain norms.

In order to be able to simulate all these processes in an agent-based model, we have chosen the following key factors and processes in HUMAT:

- Needs as the motivational driver of humans to act

- Sociality to include informational and normative influences

- Decision-making to select a course of action

- Networks as the social fabric connecting agents with shared properties

The combination of these cognitive, social-psychological and sociological factors in a computational model allows for a dynamical causal connection between the micro, meso and macro levels of social dynamics. HUMAT thus provides a basic model for combining theoretical ideas from different levels into a single framework. Other theoretical notions may be very relevant for the simulation of specific cases with specific dynamics. Therefore, a basic model should also allow for the inclusion of extensions in a theoretically meaningful and practically feasible way. This will be demonstrated in Section 3.3 i.e., "Extending HUMAT: The COVID case".

The basic HUMAT thus complements integrated models by formally linking theoretical concepts at the cognitive level (cognitive psychology), the social interaction level (social psychology) and the network level (sociology). It provides a modelling framework that links experiential, social and value needs (driving motivations) to social cognition (the perception of others), decision-making and acting on the basis of information, and finally communication (listening and speaking) through networks. The framework provides an integrated social scientific framework that conceptually links theoretical notions of different drivers and processes, and proposes formalised causal (computational) links that allow for dynamically modelling social processes. HUMAT thus could be considered a computational social theory (e.g., Nowak & Vallacher 1998).

Because of its universality, HUMAT is able to model group dynamics such as the flow of information and the establishment of norms in networks of interest groups, opinion dynamics, and subsequent behavioural dynamics such as processes of innovation diffusion. It is capable of dealing with individual decisions such as investing in a neighbourhood project, and habitual behaviours such as commuting.

The formation of networks of people with similar interests is an important social dynamic in social processes, therefore a first crucial challenge is to start with identifying how people organise themselves in groups to improve their status quo or to implement changes. The homophily principle, known commonly as “similarity attracts” and “birds of a feather flock together”, is a rule often used within social simulation models to address group formation, normative pressures and clustering effects (e.g., McPherson et al. 2006; Jager 2017). Data on: (1) how groups sharing particular interests form and grow, and (2) how groups having conflicting interests interact has to be collected, and subsequently implemented in the modelling framework. For example, a plan to reduce car traffic in a neighbourhood may be supported by people living in that neighbourhood for safety or environmental quality reasons, yet shopkeepers may fear a decline of their turnover if the traffic organisation changes. Citizens emphasising safety may discuss the issue with parents in a schoolyard, an environmental working group discussing air and noise pollution may be formed, and shopkeepers may voice their concerns through the media.

Understanding the social dynamics surrounding local planning issues requires getting a grip on the communicative processes and social influences taking place in a network of people having different and sometimes conflicting interests. Ideally, empirical data reveal what dimensions of similarity play a role in formation of such topical driven networks, and what the emergent properties of resulting networks are. Parents in schoolyards may display a spatially condensed clustered network, whereas a network of shopkeepers may assume a starlike topology, if a strong opinion leader (or formal representative) is present.

The second challenge in modelling social dynamics is to capture the communication between actors. Many social simulation models have been developed to address the conditions under which individual agents collect (social) information to make decisions. However, in communities, communication dynamics are dictated by people’s need to manage consistency associated with implementing socially innovative behaviour. For a simulated agent, this means that it should be able to experience inconsistencies between for example its own preferences (e.g., based on experience) and the social norms. That process is realised either by inquiring about (socially innovative) actions performed by other agents, or actively signalling its own preferences to other agents (e.g., people, who are motivated to convince others of their opinion). However, an agent may also engage in preference falsification, as the example in Section 3.1 shows agents may express a preference due to normative pressure. Of course, breaking a tie is also an option.

It is important to use a psychologically plausible framework to address the motivation of an agent to actively communicate to other agents in order to change their behaviour/opinions. While several opinion dynamics models introduce psychological plausible mechanisms for communication, in HUMAT this communication is a cognitively-motivated action, and as such is endogenous and rooted in the agent’s knowledge, motives, and representations of the (social) world. Outgoing communication often aims to change other peoples’ opinions and behaviour, which seeks to improve the outcomes for the sender. For example, a vegan who persuades family members to go vegan will benefit from shared cooking, norms and values. The effects of persuasion can thus be related to (expected) experiential outcomes, social connectedness and the (core) values a person holds. Therefore, HUMAT assumes that an agent’s motivation to communicate with another agent is based on a cognitive dissonance, which is expected to be reduced if the agent succeeds in convincing other agents to change their opinions and behaviour. If the communication persuades other agents to change opinion and/or behaviour, this will result in a higher multiple-need satisfaction of the agent who initiated the communication. HUMAT thus includes a motivational perspective on the process of persuasion.

In the following, the processes and factors that make up the core idea of the HUMAT are explained in a narrative way. In the Appendix, a description using the ODD protocol (Grimm et al. 2010) provides more detail on how these different processes and factors are formalised and implemented. The basic Netlogo code has been made available on Comses.org.

The core processes and factors incorporated in HUMAT

The HUMAT framework addresses individual factors and processes, the interaction taking place between agents, and the networks that connect the agents. In the following these factors and processes are explained in a more integrated narrative.

Needs

As a starting point, we address needs as the basic drivers of agent actions. Several scholars have suggested taxonomies of needs: for example, Maslow (1954) with his pyramid of needs being the most renown in this domain, but also the work of Max-Neef (1992), Kenrick et al. (2010) provide rich descriptions of the multiple needs that people have. The (anticipation of) dissatisfaction of needs serves as a driver for people to take action. When evaluating a possible attitude or action, the ability to adopt that attitude (opinion) or engage in that action (behaviour) to improve the level of need satisfaction translates into a motivation to change the attitude and/or engage in the action.

While we recognise the complexity of the human needs, especially when referring to the more abstract and time-independent needs such as self-realisation, for our modelling purposes we condense this richness into three essential needs of the agent.

Firstly, the experiential need refers to the direct experienced outcomes of an action. This may relate to e.g., the comfort of insulating a house, the danger experienced when cycling in a city with bad cycling infrastructure, the pain and side-effects of a vaccination, the financial costs of public transportation, the time it costs to vote et cetera. A financial long-term investment (e.g., insulation) may go at the cost of other pleasures (e.g., a holiday), and hence negatively affect the experiential need. These outcomes are experienced directly or anticipated in terms of rewards or punishments. The principles of classical conditioning (Pavlov 1927) and operant conditioning (Skinner 1953) can be linked to experiential needs. These outcomes also play an important role in the continuation of habitual behaviour (Jager 2000; Ouellette & Wood 1998).

Secondly, the social need refers to conformity. In the social context, most people have an urge to conform to the behaviour and opinions of others in order to avoid social exclusion. This conformity drive differs between people, and especially in the context of innovation diffusion the people with a lower importance of the social need, or people with a more anti-conformist predisposition, may play a critical role in engaging in actions or adopt opinions that go against the (local) norm (e.g., Rogers 1993). The social need directly refers to the social norm, a key component of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1985) which is often used in the context of ABM’s. Elaborate models exist targeting norms (see e.g., Melnyk et al. (2024) for recent examples), but in a context of an integrated model oftentimes a simpler implementation is needed for reasons of model transparency.

Thirdly, the value need refers to more stable, less time dependent and abstract (not directly experienced) outcomes. Examples are values related to the environment, migration, political orientations (liberal-conservative), religion, personal freedom and consumerism. They may relate to value systems as described in e.g., the Sinus Milieus (Schleer et al. 2024), which distinguishes subcultures on two dimensions, namely Lower – Middle – Upper class, and Tradition – Modernisation – Re-orientation. Values can also be related to more generic attitudes as addressed in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1985).

This simplified triple needs approach allows us to model the trade-offs that people make in their lives, as the choices they face often do not satisfy all their needs equally. For example, when you are hungry (experiential need), you may consider eating a tasty burger; however, you may also be aware of the negative impact of the meat industry on the environment and animal welfare (value need). In such situations, the behaviour of your company, ordering a burger or a vegetarian snack, may set the norm and you may comply (social need). And it is also imaginable that one person in the group having strong environmental values will signal to the group that opting for the vegetarian snack is the best choice to make. However, when you have a strong existing habit, good intentions are likely not to be enacted (e.g., Verplanken & Faess 1999).

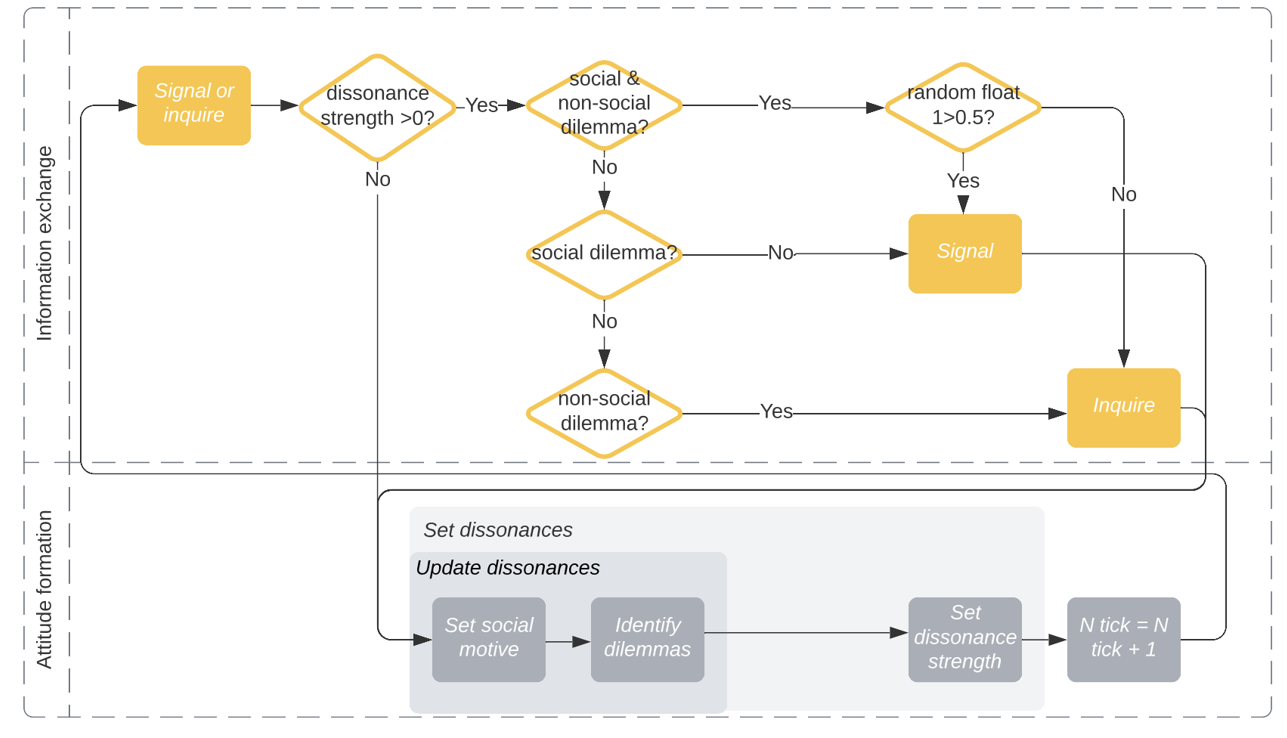

In Humat, these trade-offs between needs drive the information exchange between agents, and the attitude formation process.

Information exchange

The formation of an attitude towards an alternative, and engaging in an action will have an impact on the three needs. Often this can lead to congruent situations, for example, if cycling is a pleasant and well accommodated mode of transportation in your town, almost everyone you know is cycling, and you consider cycling as to be in line with your values on the environment and quality of life. The situation is different when there is a trade-off between the three needs, as in the example where your appetite for a burger may conflict with values and norms. If at least one need/motive is satisfied at the expense of another, the agent experiences an uncomfortable state of cognitive dissonance. This causes ambiguity and hesitation because the subject of the attitude is neither uniformly good nor uniformly bad for all relevant needs, but rather has both pros and cons. As shown in behavioural studies, cognitive dissonance is a motivational force for a change in knowledge (Festinger 1954) or behaviour (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones 2002). Consequently, the agent faces a dilemma, which may be social or non-social, and employs dissonance resolution strategies to maintain cognitive consistency.

A social dilemma occurs when the choice alternative yields either satisfaction of the experiential and value need but dissatisfaction of the social need, or satisfaction of the social need at the cost of the experiential and value need. You may for example think of a vegan student living in a student house with meat-eating friends. To resolve a social dilemma, the Humat signals to his friends and tries to persuade them to change their minds. In the example, the vegan student is trying to convince his friends that vegan food is tasty (experiential need) and good for the environment and animal wellbeing (value needs). Hence, in a social dilemma, an agent can signal to others to change their behaviour. When the other agents consider the signalling agent to be similar to them, and reputable, agents may comply to the signal, and their behaviour may change (mind this can be a cascading tipping event triggered by one signal, e.g., as in the case of a bank-run). If this does not change the situation, the dilemma remains, and the agent can break the tie(s) with other agents and connect with other agents with more similar preferences and values. The student in the example can move to a house where other vegan students are living. This example illustrates that also social networks can be modelled using the HUMAT framework.

A non-social dilemma occurs in any other instance of cognitive dissonance, where a conflict exists between the experiential and value need, and social outcomes are not really playing a role. As an example, when confronted with a lot of weeds in the garden, one may use herbicide to easily get rid of the weeds (satisfying the experiential need) but at the same time feeling bad about the negative impacts this has on nature (value need). To satisfy the value need, one must pick the weeds by hand, which is often not experienced as a pleasant activity. To resolve this non-social dilemma, the Humat inquires with alters in his ego network to find more advantages for one of the actions, or to make the already existing ones seem more important. One could be convinced that picking weed is a very mindful activity, or that herbicides hardly affect nature.

Attitude formation

Attitudes are formed on a set of beliefs that are the result of need-values. An agent revises its beliefs about alternative opinions and actions on the basis of the collected information (inquiring) about the preferences and beliefs of alters in the ego network. Once all the information is up to date, the agent compares the object of the attitude with an alternative in terms of satisfaction and dissonance level, and chooses the more preferred option. Attitudes are usually quite stable (e.g., Kiley & Vaisey 2020), but they can evolve and guide decision-making or other forms of behaviour. For example, a farmer who is already convinced of the importance of biological farming (the farmers’ needs value) may finally make the decision to switch towards biological farming, accepting a lower profit, after learning about the link between certain pesticides (organochlorines) and Parkinson’s disease. A new preference for an action or opinion will replace the (habitual) action or opinion chosen at a previous time step only if it is significantly more satisfying and less dissonant.

The objects of comparison, i.e., the choice alternatives available to the agents, are defined by the researcher and are determined by the case being modelled. In the basic version of the HUMAT framework there are two alternatives to choose between, e.g., voting in a referendum to close a park to car traffic (Jager et al. 2024) or taking a vaccination or not (Li & Jager 2023). HUMAT is also suitable for modelling choice behaviour in contexts with multiple alternatives. This can address situations with new options, such as the entry of a new product or technology into an existing market, but also the choice between different modes of transportation. For example, different conditions such as weather, traffic intensity and fares may influence the choice between cycling, driving or public transport.

Social networks

Human social networks are dazzlingly complex. Many different qualities of information are being produced, distributed through a great variety of channels, and ignored, accepted and perhaps shared. For example, we observe what kind of cars other people drive, we have access to other people’s experiences through reviews and social media, algorithms developed by engineers decide what (emotion eliciting) content and opinions are being fed to you, short conversations express a preference in, say, a schoolyard, and you may have engaging discussions around the dinner table about appropriate behaviour. Even smell and visual appearance can have large implications in network exchanges, and it is clear that a great deal of simplification is needed in modelling these networks.

The key step of the HUMAT framework is that we do not try to impose a network on our population of agents, but we rather leave it to our agents to decide who to connect with, and how to interact. Here, similarity and reputation are important factors.

For different cases one can think of different settings for the agents to connect to other agents. For example, a case about a local solar project might focus primarily on the people living in that district, along with some opinion leaders. Low involvement might lead to limited interaction. Conversely, issues that raise a lot of concern, such as climate change or a pandemic, may result in a lot of interactions, including social media, and opinion leaders may have an excessive impact on the opinion dynamics. For any HUMAT application, the modeller should reflect on the similarity and reputation factors that can be used to determine the likelihood of agents connecting, and the average and distribution of connections that agents have. This should be used to initialise the network. Depending on the purpose of the model, it can be decided whether the agents can rearrange their network, e.g., by adding or deleting links as a function of changing opinions.

Examples of HUMAT Implementations

In this section, we will briefly discuss three implementations of HUMAT to give an idea of how this framework can be used in projects addressing more generic or specific cases. However, HUMAT is now being used in several other projects as well, covering different domains2. The first case will address a very stylised model of opinion dynamics in a community, the second is an implementation of HUMAT in an empirical case of a city-wide referendum, and the third is an extension of HUMAT that shows how additional psychological processes can be implemented to study social dynamics, in this case about Covid vaccinations.

Using HUMAT for a stylized model of community opinion dynamics: The Dialogue Tool

Many proposed projects at a community level have an impact on the citizens in a community. If a municipality wants to block transit traffic on a major road, or proposes to move towards a more nature-inclusive management of public green spaces or towards district heating, heated discussions may ensue between those in favour of a plan and those who oppose it. In a vibrant democracy, a dialogue is essential to exchange information, perceptions and interests in order to come to a solution that maximises the satisfaction of the community. However, we often observe that such processes can lead to frustration due to polarisation between different groups, the neglect of the most vulnerable people in a community, and the dominance of people who have a lot of influence in the community. Such outcomes can damage the social fabric of communities and undermine problem solving.

In democracy-labs, citizens are increasingly invited to actively participate in community sessions to discuss different perspectives and interests in tackling problems they face. In supporting people to develop a perspective on the interests of all the people in the community, we developed the Dialogue tool to help citizens to transcend their individual interest in a case, becoming more aware of the diverse perspectives in a community (Jager & Wang 2023; Wang & Jager 2024). This tool allows people to visualise different scenarios and contexts, making them more aware of unfavourable outcomes for the community as a whole. By encouraging a more inclusive dialogue, we empower citizens to engage with diverse viewpoints and think about the wider impact of their choices. In initial field studies, we have explored how a stylised simulation model based on HUMAT can help to raise awareness of the social dynamics that can emerge in a community, and how an interface could be simple enough for non-modellers to use comfortably.

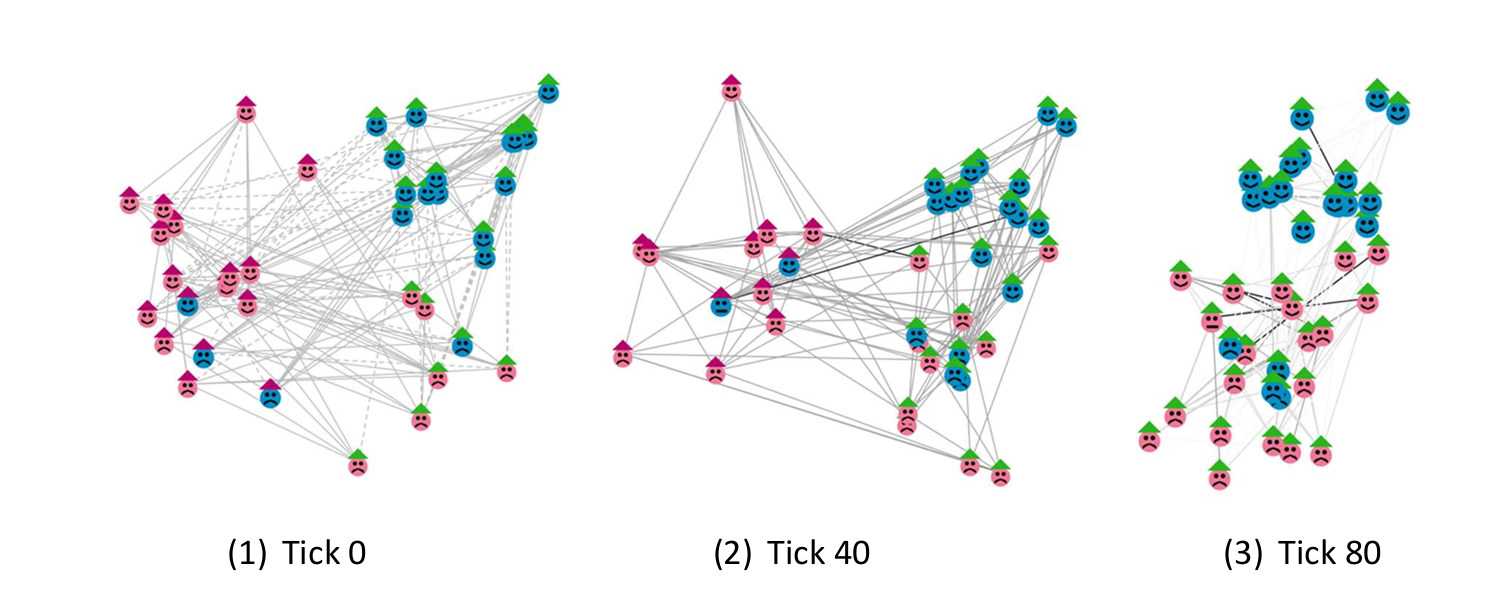

In the Dialogue tool, the HUMAT framework is determining the social dynamics emerging in the simulated community. For the users, the Dialogue tool uses the following symbolic visualisation:

- Individual agents are symbolised by nodes or heads.

- The relationships between these agents are represented by connecting lines or edges. "Dashed lines" signify connections between different groups, while "solid lines" depict connections within the same group.

- Distinct groups are identified by the colour of each agent’s face.

- The specific opinions of agents are indicated by the colour of their hats, denoted as either "green" or "red."

- The importance of agents’ verbal contributions is reflected in the size of their representations.

- Facial expressions, depicted as happy, sad, or neutral faces, convey the satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or indifference experienced by these agents.

In the following visualisation, the community is spatially distributed. The more satisfied agents are on top, the less satisfied below. Supporters of a plan are positioned on the right, and the opposition on the left. The further to the right an agent is, the stronger their support; the further to the left, the stronger their opposition. Two different coloured groups can be seen having different interests and opinions. After some time, all of the agents support the plan, wearing a green hat. However, we also observe that a significant part of the community is unsatisfied despite supporting the plan. This simulation highlights that due to social pressure many (more vulnerable) people may support a plan, despite personally not being truly satisfied with it. Such an outcome could incite a discussion on how to change a plan to improve the satisfaction of many citizens.

It is possible for every agent to follow their internal processes, their experienced dissonance, their interactions with other agents and their motivation to form new links and terminate others. However, for the practical use, this would result in an overwhelming interface.

For the use of this Dialogue Tool, we envisage three different levels. The first level addresses some stylised simulation runs that demonstrate some typical social dynamics, such as presented in the example. In the following video aimed at citizens, the basic model is explained and three typical outcomes discussed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUZDoMmCnCw. This simple model is also available as a Netlogo model with very limited options in the interface.

For those who want to get closer to their own community, and add groups of different sizes, preferences and influence, a model adding more settings in the interface is provided. In our first field tests, non-modellers were capable of setting up and running a model for their case within an hour.

For interested citizens and policy makers that want to go deeper in a specific case, also a Netlogo model is provided with even more possibilities to simulate a community, define opinion leaders, and test some basic policies aimed at communication and plan adjustment.

The models and videos produced for the INCITE-DEM project are publicly available at: https://incite-dem.eu

Using data in simulating an empirical case: The Groningen case

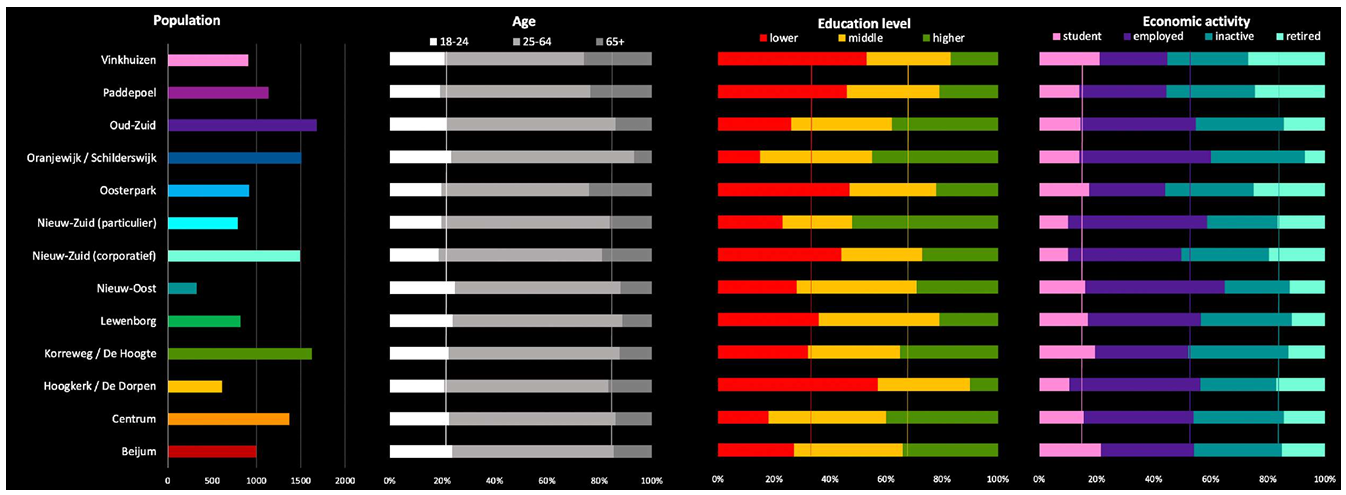

HUMAT has in its testing phase been used to simulate empirical cases. One very interesting case was the 1994 referendum in Groningen on closing a main street through a park for car traffic, which in reality resulted in a victory for the pro-closure supporters of 50,9%. Considering this was a referendum in which all of the citizens had a vote, but different interests depending on where they lived, and different perspectives related to age, education, income and occupation, we started with building a synthetic population (see Jager et al. 2024). For 13 neighbourhoods we made a categorisation for the number of citizens, their age (3 categories), education level (3 categories) and economic activity (4 options).

We created 14.165 agents, having a 1/10 scale of the 141.653 citizens living in Groningen in the year of the referendum. Historical data on this carefully studied referendum (Municipality of Groningen 1994; Tsubohara 2007) allowed us to make grounded assumptions on how spatial location, age, education level and economic activity affected the opinion in favour or against the closure of the park. As a result, the Groningen case was calibrated to the empirical case with respect to: a) timeline of particular relevant events and b) geo-socio-demographic characteristics of the resident population. Figure 3 shows the different neighbourhoods and their opinions in favour (green) of against (red) closure of the park.

Based on spatial location, age, education level and economic activity, a static network was constructed to connect the agents. The agents could experience dissonances between for example their personal preference and the opinion of their connections, resulting in interactions and opinion changes. Thereby, the model captures both motives/needs of the residents that are addressed by the social innovation (Antosz et al. 2019), and social networks of residents (Antosz et al. 2020). The design allows for simultaneous integration of methods, because the agent-based modelling serves as a conceptual and formal framework for merging findings from other methods and data collection techniques, showcasing a holistic integrated mixed-method design (Caracelli & Greene 1997).

The parameterisation of the model aimed to replicate the ultimate vote and turnout at the neighbourhood level (see Bouman et al. 2021). After 1000 runs, which produced a normal distribution peaking at 49.54 with SD 0.72 for the vote, we found that slightly more than 50% of the runs resulted in a victory for the people against the closure. All 1000 simulation runs produced an almost equal number of votes for and against closure. Additional experiments were conducted testing the effects of campaigning (by shopkeepers or the municipality) and of an accident that activates the need for safety. These experiments demonstrated the volatility of the opinion dynamics, as interventions such as informational campaigns and town hall meetings easily tipped the outcome of the referendum to a substantial number of pro-closure voters. This shows that deliberative persuasive acts by local authorities and critical events can have a strong influence on the acceptance of the innovation.

This application of HUMAT demonstrated to be capable of using a variety of data in a simplified setting to produce a case simulation that was producing realistic output.

HUMAT as an integrated framework should make it possible to connect additional mechanisms to the basic framework in a logical manner. For example, when the empirical data indicated a strong bimodal distribution of opinions on vaccination3 against Covid-19, unrealistic perceptions of risks regarding hospitalisation when contracting the disease and side-effects of vaccination, we were wondering about the mechanisms contributing to this problematic case of opinion dynamics, realising that the damage to the social fabric of our society was significant (Li & Jager 2023).

Three additional mechanisms were added to the basic HUMAT framework. First, we added the availability heuristic, which implies that information that is more often heard is more likely to be accepted. News channels that had a tendency to share sensational news to keep their viewers may have been responsible for the general public to overestimate risks. Secondly, people are more likely to accept information that they more agree with than with conflicting information. This confirmation bias would cause people to have a tendency to stand their ground regarding their opinion. Finally, the fear of the disease and the fear of the vaccination both strengthen people’s tendency to abide by the opinions of (different) authorities.

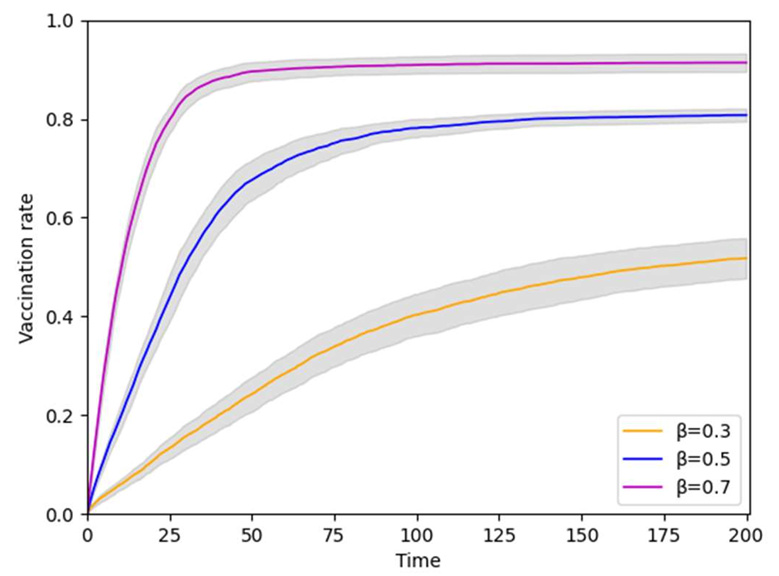

A simulation experiment was conducted to examine whether changes in disease severity (\(\beta\)) influence vaccination rates. The underlying assumption is that as the severity of the disease increases, the fear of its health consequences also intensifies. Figure 4 shows that the higher the perceived risk of the disease (higher \(\beta\) value), the more likely it is that people get vaccinated.

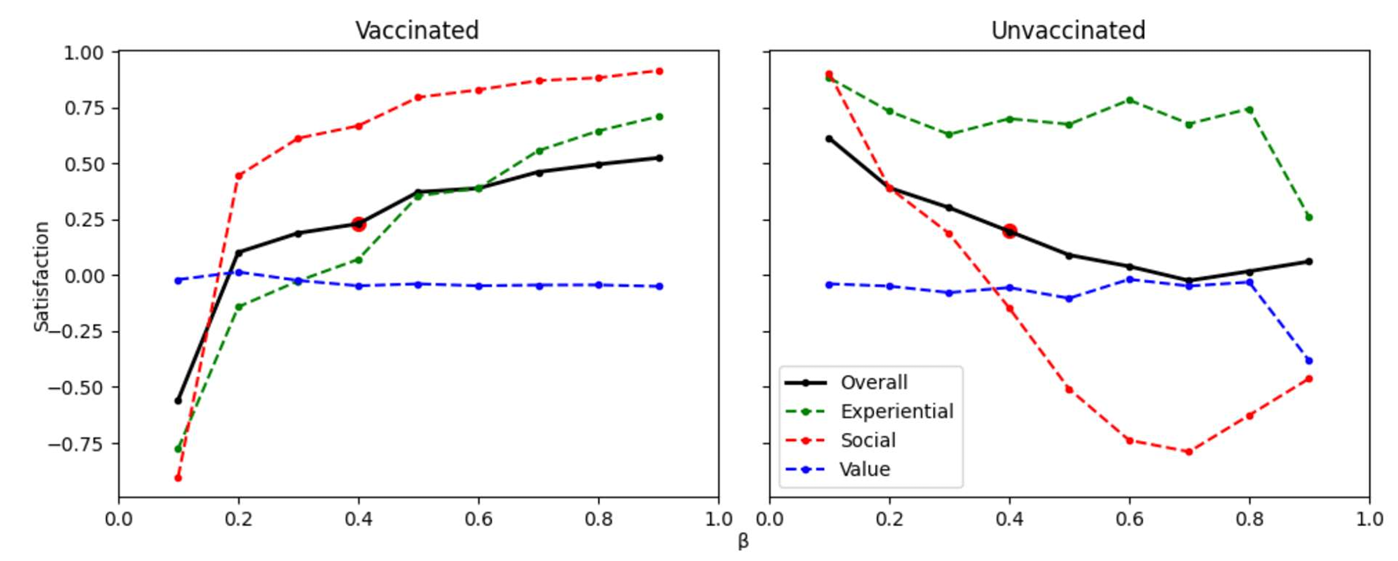

Interestingly, we also observe varying effects of disease severity on the satisfaction of the vaccinated and unvaccinated people. Figure 5 below presents the different satisfaction levels (overall, experiential, social and value needs) for runs where we vary the severity of the disease (higher \(\beta\) value). Overall, the results indicate that as \(\beta\) increases, the overall satisfaction of the vaccinated group improves, while the satisfaction of the unvaccinated group declines slightly. Among the three types of needs, social needs had the strongest impact on satisfaction for both groups, especially the unvaccinated. This is because, as disease severity rises, more individuals in their social networks become vaccinated, causing unvaccinated individuals to experience social pressure, which reduces their social satisfaction. The dissonances that occur in the networks give rise to a lot of interactions between agents.

The results of this simulation study suggest that the empirical overestimation of risks of both Covid-19 and the side effects of vaccination can be explained by the impact of fear on information processing and availability heuristics. Furthermore, such cognitive mechanisms can contribute to social polarisation. Confirmation bias, for example, was responsible for an unbalanced polarisation: while a majority group supports vaccination, a minority group strongly opposed it.

This implementation of HUMAT demonstrates its flexibility regarding the incorporation of mechanisms that one would like to explore in a given case.

An integrated modelling framework

The HUMAT framework integrates a number of key processes and drivers on the level of individual cognition, social interaction and social networks. Whereas on each of these levels much more sophisticated and detailed insights and theories are available that in principle could be formalised in a simulation model, at this stage HUMAT is already confronting the potential user with a challenging rich modelling framework. The HUMAT framework has now been applied to model a number of cases, such as a referendum on closing a road for car traffic, cities closing city-blocks for transit traffic (see Bouman et al. (2021) for a series of HUMAT applications), opinion dynamics regarding Covid-19 vaccination (Li & Jager 2023) and social distancing rules during a pandemic (De Vries et al. 2023).

Use and outputs

The outputs of running a HUMAT based simulation can be manifold. In section 2 of this paper we provided a number of minimal outputs to demonstrate processes happening in artificial societies. However, when a specific case is being modelled, the model user can decide to monitor a large number of variables to follow the social dynamics taking place and the impacts of policy interventions and critical incidents. Concerning the output, we can distinguish between (1) studying the processes taking place in individual runs, (2) inspect results over a large series of runs, possibly using an experimental design, but it is also possible and even recommendable to (3) inspect the processes that take place in the life-histories of individual agents.

Key variables that can be followed using a single run are

- The changes in behaviour/opinions/choices of Humats over time, and polarisation/convergence that may happen between (groups of) agents.

- The level of need satisfaction for the different Humats (e.g., related to social-economic status) over time

- The cognitive processing (degree of dissonance) and decision-making taking place in the simulated society over time. In particular the relation between developing dissonances as a precursor of social tipping points can be investigated

- The variables/processes above in relation to different types of incidents, policy interventions, innovations (e.g., new technology) and informational influences by opinion leaders (hubs).

- The identification of segments of agents that respond differently to policies.

Inspecting multiple runs allows for collecting more aggregate data for analysis, such as

- Identification of the distributions of possible outcomes of a process (e.g., normal or multimodal distributions), indicating the likelihood of certain scenarios to happen (identifying a landscape of transitional pathways and attractor points/solutions)

- Identifying the robustness of the simulation results for changes of settings (sensitivity analysis)

- Identification of tipping points in a social system, and analysing what parameters play a key role in what order in reaching a tipping point.

- Systematic analysis of the impact of policies on the likeliness of certain scenarios.

- Identification of sequences of policies that outperform other sequences (e.g., info first followed by pricing, or the other way around)

Finally, also the life histories of individual agents can be studied in detail, for example concerning:

- The development of need satisfaction and associated cognitive processes (dissonance), thus identifying individual tipping points (personal transition) within different types of agents (e.g., involvement, socio economic status) leading to a change in behaviour/opinion or action (e.g., becoming a vegan).

- The identification of agent types (segmentation on involvement, socio-economic status) that are susceptible for particular types of policies, thus allowing for targeting specific groups of agents (e.g., innovators) with policies, and exploring social cascading effects to other groups of agents (early adopters).

Data for parameterisation

In parameterising a simulation of a specific case, the properties of the population or community under investigation have to be represented in the generic model. Various data sources can be used to construct a representative artificial population. Here, HUMAT offers a practical template, as the integrated framework supports the systematic identification of processes and drivers relevant for a specific case. These cases may differ concerning the behavioural context. For example, habitual behaviours, such as dietary choices and mobility patterns, are different from single decisions, such as joining a heat network or casting a vote in a referendum. Here the HUMAT framework also guides the search for suitable data sources supporting the parameterisation of the model. Some of these data sources will be quantitative, such as statistics on socio-demographics and surveys (existing data, or data collected for parameterising this case) on population opinions. Data from micro-simulations, where the characteristics of a population are available at the individual level, are very suitable for constructing an artificial population for a case (see e.g., Bouman et al. 2021). These sources produce distributions for parameterisation of the agent population, e.g. regarding age, household composition, education, income, occupation and geographical location. However, qualitative data is also important. In many social systems a few large influencers (also referred to as opinion leaders or hubs) are present. The social outreach of people in a society usually follows a power-law distribution, where many people have a limited influence, and a very few people have a lot of influence. In practical cases this can be observed as influencers being present in the media, and having a lot of followers on social media. Such influencers are unlikely to be captured in representative surveys. Yet such celebrities, politicians and other famous and reputable people have a strong impact on the opinions and behaviour in a society. Here qualitative data are indispensable to identify such influencers and represent their influence in a simulation model. The type of available and collectable data does of course determine the degree of specification that can be obtained when modelling a specific case.

Implementation

HUMAT model implementations do not require a precise specification of all model components in order to run. How much specification is needed depends on case study, the questions being asked and the audience and users of model output. For example, when modelling one-shot behaviour, like the dynamics of starting and joining a heat-network, habits do not play an important role, but social communication in the target district of the project does. On the contrary, when addressing repetitive behaviour such as grocery shopping, habits will play an important role in e.g. understanding the critical dynamics of a change towards a more plant-based diet. When a model is being used to demonstrate the stylised fact of how norms affect innovation diffusion, an almost empty model (no empirical parameterisation) would suffice. However, if the goal is to support a discussion on the possible outcomes of a specific citizen initiative for city improvement, simulated scenarios should be precise in order not to miss important opinion and behavioural drivers, to include relevant subgroups having different interests and opinions, and to identify and address important influencers and opinion leaders.

An advantage of HUMAT’s integrated setup is that from its “empty” starting model it can be filled with data to make components more empirically grounded. Moreover, once a certain model component is in place, it can be used for different modelling projects (reusability). When the demographics of a neighbourhood, village or city have been represented as a micro-simulation component, this can be easily used for other projects addressing the same population as well. Or when a new component has been added to the framework, such as fear, this component can be used in other domains where fear is a factor as well. In such situations, a sub-process of the HUMAT framework can be modelled in more detail to explore how more specific drivers and processes may affect the dynamics of the social system. As a metaphor, one can think of a Lego puppet made with many sizes of bricks, from very small to large. If in a simple model the head is composed of a single large brick, you can make the model more detailed by rebuilding the head with smaller bricks (specific theories). However, this does not affect the legs of the Lego puppet. And if an element has been forgotten, such as a working hand, it is easy to connect a new hand to the existing puppet4.

The HUMAT simulation framework is limited concerning the theoretical concepts that have been included so far. For example, the processing of information as a function of involvement and source effects has been implemented in a simple way. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Petty & Cacioppo (1986) offers a more specific perspective for that, and more refined implementations of that theory are already available, e.g. in Mosler (2006). Emotions also are not explicitly modelled in the HUMAT. For example, fear could conceptually be connected with the (expected) changes in different needs of the agents. Fear in particular may trigger social processes, and Epstein’s Agent_Zero (Epstein 2014) implementation of fear may contribute to bringing in a cognitive or neuroscientific basis for modelling fear in HUMAT. Also, the emotion of hope seems to play an important role in the expectations people have from the possible impact of plans. Furthermore, very specific theoretical mechanisms can be implemented. For example, in Li & Jager (2023), the availability heuristic is being implemented to simulate how media coverage on Covid-19 influences the risk perceptions for both the disease and the vaccination side-effects. Also the confirmation bias has been implemented to capture the tendency of people to disregard information that is dissonant with their choice. The key point here is that the HUMAT framework is flexible to incorporate such mechanisms into a computational model in a theoretically consistent way. Because of the integrated theoretical structure of HUMAT, additional mechanisms can be implemented logically within the existing framework.

Could a framework like HUMAT become a theory?

Social simulation is the key methodology in generative social science (Epstein 2006), and HUMAT aims to provide an integrated generic model to support the development of social simulations. Considering the ongoing discussion on whether and when models can be understood as theories, we would like to conclude with a reflection on the theoretical contribution of the HUMAT framework.

From a social science point of view, a theory is a systematic explanation of a social phenomenon. A general principle in the social sciences is that a theory allows for making correct predictions about the outcomes of a well-defined experiment, and hence replication is a key principle in the establishment of social scientific theories. Therefore, much theoretical development within the social sciences relies on well defined, controllable and replicable experiments in lab settings.

A systematic study of the social dynamics in larger populations over longer periods of time runs into a number of problems from a traditional social scientific perspective. The first problem is the lack of experimental control. Because social dynamics are multifactorial, evolve over time and take place in an open system setting, a classical controlled experimental approach is not applicable. Whereas qualitative analysis of practical cases is very well possible and meaningful, this does not mean that a specific situation can be replicated, let alone be precisely repeated with a controlled experimental intervention. This is one of the reasons why social simulation is gaining momentum, as it does allow for conducting experiments with larger simulated populations over prolonged periods of time with perfect experimental control, albeit that the realism of the generated social dynamics is difficult to establish.

This brings us to the second, perhaps more fundamental problem, which relates to the complex nature of social dynamics. Imagine that we would be capable of replicating a real live case of social dynamics multiple times in a controlled lab situation. A theory in a traditional social scientific sense should be capable of predicting the social dynamics taking place given a certain initial (experimental) condition. If the proposed theory does not correctly predict the outcomes, additional variables should be included or the weighting of factors should be adjusted. This is essentially an approach that reflects a mechanical Laplacian worldview (Laplace 1902): if all parts (variables) of the clockwork (theoretical model) are in place (weighted), a perfect prediction can be made. However, this predictability confronts us with a fundamental problem, as the dynamics in social systems are complex by nature. As Lorenz (1963) demonstrated for meteorology, small causes may have large effects in such systems. And ultimately, these small causes bear a fundamental uncertainty, which can be related to Heisenbergs’s uncertainty theorem (Heisenberg 1927).

This fundamental uncertainty applies to social systems in turbulence, such as revolutions, disruptive innovations, hypes, fashions and other tipping-point-like situations where radically different futures can emerge. The course of the developments can be strongly influenced by a few or sometimes even a single person. For example, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip was a matter of chance, but served as an important trigger in cascading into the first world war. In many social innovation projects, such chance events may prove to be critical in determining their success or failure.

To be clear, this fundamental uncertainty does not mean that behaviour in social systems is not predictable. On the contrary, social complex systems are usually quite stable, and habits and norms serve as stabilising forces. Self-organising forces can give rise to quite stable patterns and sometimes even lock-ins (Heylighen 1997). These homeostasises often allow for predicting how an intervention results in temporal and limited changes in behaviour. Especially within the field of marketing elaborate statistical models are being used to predict for example changes of market shares as a result of pricing and advertising strategies.

However, a more generic social science theory should not only explain predictable phenomena, but definitely also explain the fundamental uncertain transitional dynamics as mentioned. Many societal challenges deal with uncertain behavioural transitional pathways, such as adapting to changing climate conditions, energy transition, transitions in food systems, adaptation to AI in society, mitigating dynamics of migration and acculturation, to name a few current examples. In the context of these developments, many cases of behavioural change address transitional dynamics in social systems. Here the (predictable) homeostasis is temporarily entering a turbulent (unpredictable) situation, and the social system may transition towards a new homeostasis with new patterns of behaviour. The occurrence of such tipping points was discovered in studying the sometimes abrupt transitions in ecological systems, and awareness has risen that in many complex systems such transitional dynamics happen (Kurahashi et al. 2023; Scheffer 2009). Such transitional dynamics are addressed as phase-transitions in physics, and in socio-ecological systems the concept of tipping points is often used (Nyborg et al. 2016).

Social simulation models, such as HUMAT, offer the social sciences the suitable tools for studying the complex dynamics of transitions such as revolutions, disruptive innovations, hypes and fashions. However, in a classical social scientific perspective it is problematic to qualify such models as “dynamical social theories”. Whereas it is possible to test model performance by replicating historical cases of social complex dynamics, which would qualify as an empirical validation in a classical social scientific perspective, we have to acknowledge that the empirical data to validate a model against could have been radically different. The key point here is that a historical transition could have followed different pathways and produced different outcomes. Replicating a single manifestation of reality whilst not knowing how many alternative realities could have been manifested is not a solid validation from a complexity perspective. Hence this replication of the past as a test for the predictive capability of a model is methodologically not sufficient to validate a model as a theory. To complicate things further, models that capture different causal processes and initial conditions still may arrive at similar outcomes (von Bertalanffy 1968). This refers to the problem of equifinality (Poile & Safayeni 2016).

Given that future transitional social dynamics confront us with multiple potential pathways, the predictive capacity of social simulation models is fundamentally limited, and different models may produce similar ranges of outcomes. Does this mean that a valid theory of social dynamics is impossible, or do we need to depart from the classical social science definition of what a theory is?

Poile & Safayeni (2016) mention “reasonable assumptions” as a criterion for building a theory using social simulation. This refers to the choices made when operationalising theoretical (abstract) concepts into processes and initial conditions in the model. And indeed, in the HUMAT framework many theory-based, and hence seemingly reasonable, assumptions are being made on the drivers and processes guiding the agents’ actions. However, also here caution is needed, as for example Muelder & Filatova (2018) demonstrated that the Theory of Planned Behaviour could be implemented in different reasonable ways, leading to different outcomes of the simulations. Moreover, consciousness and emotions, being essential to human life, may be very difficult to capture in reasonable computational code.

Graebner (Graebner 2018, sec. 1.6) states that “on the meta-theoretical level, there is no consensus on questions such as (1)”Is it necessary to verify and/or validate a model?“, (2)”To what extent is the verification and validation of a model even possible?“, or (3)”If model verification and validation are needed, what kind of verification and validation is adequate for the model at hand?" An epistemological perspective is important in discussing the value of modelling, and in discussing if and when social simulation models such as HUMAT can be considered to be a theory.

At this stage, we remain inconclusive about the question whether frameworks such as HUMAT can become a theory. However, we would like to conclude by referring to the action research perspective of Kurt Lewin (Greenwood & Levin 1998). Two quotes from Lewin are especially relevant in this context: “Nothing is as practical as a good theory,” and “the best way to understand something is to try to change it.” (Greenwood & Levin 1998, p. 19). For applications of HUMAT this means that it should prove its value in actual cases where it is being used in the context of policy development and implementation. Whilst HUMAT has successfully been used to model a number of successful cases of social innovation (Bouman et al. 2021), its theoretical value will only become visible if it can be successfully used in practice to anticipate social dynamics, and suggest successful mitigation strategies. Projects are now underway in which local communities engage with models to reflect on their own social dynamics in the context of environmental policies, hopefully contributing to a strengthening of local democratic processes, thus living up to the perspective on theories as provided by Kurt Lewin.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Doug Salt, Amparo Alonso-Betanzos, Noelia Sánchez-Maroño, Bertha Guijarro- Berdiñas, Alejandro Rodríguez and Christian Klöckner for the valuable discussions and review of the ideas shared in this publication. The research being conducted for this publication has been funded by the EU Horizon2020 programme SMARTEES, Grant Agreement No 763912 and by EU Horizon 2020 project INCITE-DEM, Grant Agreement 101094258. The case study presented in section 3.1 has been conducted within the INCITE-DEM project, funded by EU Horizon 2020 programme, INCITE-DEM, Grant Agreement ID: 101094258. The case study presented in Section 3.3 has been supported by the China Scholarship Council (grant agreement no. 202206760072). Finally, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of JASSS for their rich and valuable comments on a previous version of this paper, and Flaminio Squazzoni for his meticulous proofreading.Notes

- The name HUMAT is inspired by the simulated animals of Wilson (1991), called Animats.↩︎

- Current EU projects where HUMAT is being used are PHOENIX (https://phoenix-horizon.eu), INCITE-DEM (https://incite-dem.eu), CHORIZO (https://chorizoproject.eu/), URBANE (https://www.urbane-horizoneurope.eu/), INNOAQUA (https://innoaquaproject.eu/), PRO-CLIMATE (https://pro-climate.eu/).↩︎

- Strictly spoken the mRNA injections were not vaccinations, but we comply here to the commonly used wording↩︎

- We are not the first to liken this kind of process to children’s toys – Parker et al. (2008) outline the MRPOTATOHEAD framework of components for agent-based models of land use change to consider implementing↩︎

- New terms for function parameters had to be specified in the Netlogo reporter as the commonly used terms were used as primitives. As a result, mean was substituted with mid, std with dev, min with mmin, max with mmax).↩︎

Appendix: Overview, Design Concepts and Details of the HUMAT Framework

Overview

First, we will provide an overview of the purpose and patterns of the HUMAT framework, followed by a presentation of the entities, state variables and scales in the framework. This section will conclude with a description of the process overview and scheduling.

Purpose and patterns

The purpose of the HUMAT framework is to represent the socio-cognitive process of attitude formation and behaviour selection. The subjects of the attitude are decided by the modeller to fit the research problem that the agent-based model investigates. In the simplest version of the framework described here, Humats (we use ‘HUMAT’ for the framework, but ‘Humat’ to denote an implemented agent) form attitudes towards two alternatives, A and B, and choose the preferred option. In principle, more alternatives can be offered to the agents, and the selection of an alternative can address the behaviour of an agent, e.g., voting, purchasing (products) and performing (e.g. consuming).

Entities, state variables and scales

The model contains a single class of entity, the ‘HUMAT’, representing an individual in a population. The number of agents is a model parameter to be adjusted by the modeller. The framework is predicated on agents having a choice between two options. There are therefore two sets of state variables – those with one state variable per option (Table 1), and other variables (Table 2). Importantly, each agent is characterised by a set of needs/motives that are important for the subject of the attitude. The framework proposes three groups of motives that play an important role in any process of information diffusion over social networks and subsequent attitude formation: experiential needs, social needs and values. Agents vary with respect to how important each group of motives is. Moreover, agents have a set of beliefs about how the subject of the attitude satisfies those motives. In an implementation of the framework, the number and type of motives can be adjusted to the modelled case. For example, the researcher might decide that three different experiential needs and five different values are relevant for the modelled case, or that only two experiential needs matter, and values are altogether irrelevant. Links between the agents denote communication acts, i.e., sharing information about the subject of the attitude. In the basic version of the HUMAT framework, the links are created based on the proximity that represents homophily with respect to physical space, as each agent is characterised by a location in a two-dimensional world. However, in an implementation of the framework the number of networks and homophily rules can be adjusted to the modelled case.

| Variable name | Description | Values | Changes? |

|---|---|---|---|

| #same-choice | Number of alters with the same choice in the ego network as perceived by ego | Non-negative integer | Yes |

| Chosen | Alternative chosen | {A, B} | Yes |

| aspiration-level | The extent to which copying this Humat’s choice is appealing to other Humats: an objective value used for the calculation of the relative aspiration level in an interaction between two Humats | [0, 1] | No |

| experiential-importance | Importance of the experiential need, individual difference | [0, 1], sampled from truncated \(N(0.5, 0.14)\) | No |

| social-importance | Importance of the social need, individual difference | [0, 1], sampled from truncated \(N(0.5, 0.14)\) | No |

| values-importance | Importance of values, individual difference | [0, 1], sampled from truncated \(N(0.5, 0.14)\) | No |

| experiential-evaluation | \(\dots\) of the chosen alternative | [-1, 1] | Yes |

| social-evaluation | \(\dots\) of the chosen alternative | [-1, 1] | Yes |

| values-evaluation | \(\dots\) of the chosen alternative | [-1, 1] | Yes |

| Satisfaction | \(\dots\) of the chosen alternative | [-1, 1] | Yes |

| dissonance-tolerance | individual difference in tolerating dissonance before they evoke dissonance reduction strategies | [0, 1], sampled from truncated \(N(0.5, 0.14)\) | No |

| dissonance-strength | \(\dots\) of the chosen alternative | [0, 1] | Yes |

| dilemma-social? | The existence of a social dilemma that a chosen alternative A/B evokes | {0 (no dilemma), 1 (dilemma)} | Yes |

| dilemma-non-social? | The existence of a non-social dilemma that a chosen alternative A/B evokes | {0 (no dilemma), 1 (dilemma)} | Yes |

| alter-representation-list | List of data ego stores about the alters in their social network. | See Table 3 | Yes |

| inquiring-list | Sort of alter-representation-list (see set alter representations submodel) | See Table 3 | Yes |

| signaling-list | Sort of alter-representation-list (see set alter representations submodel) | See Table 3 | Yes |

| inquired-humat | List of information about the alter ego inquires of | See Table 3 | Yes |

| inquiring-humat | List of information about the alter inquiring of ego | See Table 3 | Yes |